Amy Fay

Bayou Goula, Louisiana, 1844 - 1928, Watertown, Massachusetts

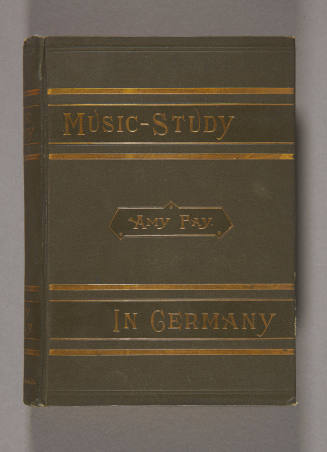

In 1862 she moved to Cambridge, where she lived for seven years with her sister Zina (Melusina Fay Peirce), who was married to the distinguished philosopher Charles Sanders Peirce, founder of the school of American pragmaticism. While living in Cambridge she studied piano with Otto Dresel at the New England Conservatory and had a tutorial in Bach with the well-known composer and Harvard professor John Knowles Paine. Paine encouraged her to go to Germany for music instruction with Carl Tausig, the great pianist and famous pupil of Franz Liszt. Between 1869 and 1874 Fay studied in Germany under the most distinguished figures in the musical world: Tausig, Theodor Kullak, Liszt, and Ludwig Deppe. Her period of study with Liszt in the spring and summer of 1873 was a high point of her time abroad, and her letters home describing Liszt as a teacher earned her international recognition when they were published, first in the Atlantic Monthly and later in her book of musical memoirs, Music Study in Germany (1881). She completed her student period with the famous pedagogue Ludwig Deppe.

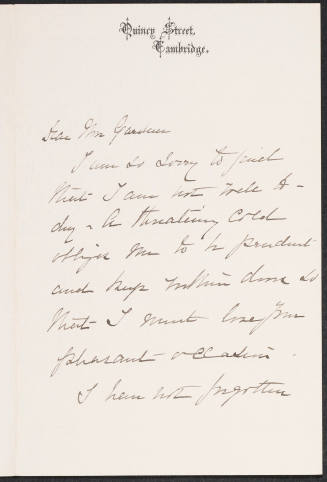

While in Germany, Fay became despondent over two losses, one personal and one professional. The first was the sudden death of her sweetheart, Benjamin Mills Peirce, the younger brother of Charles Sanders Peirce. The second was Tausig's departure from his conservatory and his subsequent death. The termination of two significant affiliations precipitated a vulnerability to nervousness that had a lasting effect on Fay, even threatening to destroy her career as a concert pianist. For more than a decade she was plagued by nerves. "I am such a nervous creature . . . that the least thing gives me a violent headache, or robs me of sleep; even a call upsets me, if the person is animated or excited," she wrote home in 1871. Similarly, in 1873, when Kullak invited her to play in a public concert, she wrote home: "With my nervousness, I thought I had better not attempt such a thing, until I had some experience in public playing." At pivotal moments inviting professional advancement Fay frequently, albeit unconsciously, seemed to "choose" nervousness, a pattern that continued for several years following her return home. In resorting to illness as a way to express her feelings of loss over the severance of significant affiliations, Fay was in the company of other nineteenth-century women of similar class and background who, in succumbing to "nerves," found an outlet for dissatisfaction with life as they experienced it. Fay, however, wanted to overcome her susceptibility to nervousness. Most of the time she summoned the resolve to accept engagements to play, but it was hard for her to control her difficulties with nerves.

In 1873, while studying with Liszt in Weimar, she met Camille Gurickx, a young Belgian student pianist who was also in Weimar to study with the famous maestro. A romantic friendship ensued, and despite an earlier decision never to marry or even do housework if she could help it, Fay became engaged to Gurickx. Some years later, however, for reasons that remain unknown, Fay's brother Norman (Charles Norman Fay), a prominent Chicago businessman and future founder of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, insisted that she break the engagement.

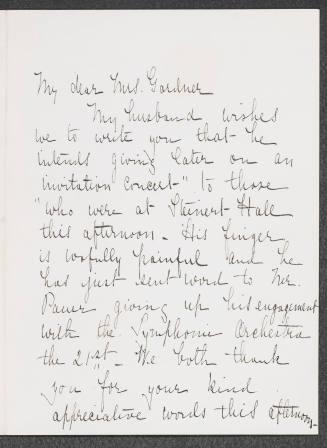

When she returned home in 1875, Fay soon received recognition as a concert pianist from a public not aware of her long-standing struggles with nervousness. She made her hometown debut in Cambridge on 19 January 1876, receiving a highly complimentary review from the nation's leading music critic, John Sullivan Dwight. In the summer of 1876, during a European sojourn undertaken with her sister Zina, she enjoyed a reunion with Liszt. The next year, she appeared at Sanders Hall in Cambridge as guest soloist with the renowned Theodore Thomas Orchestra, performing the Chopin F Minor Piano Concerto, but as had happened so often before, nervousness marred her performance. For years to come the intermittent bouts with nerves that had begun during her student days in Germany plagued her. Not until her Chicago years did she at last overcome her difficulties. Meanwhile she continued to perform in public, despite her apprehension. In September 1878 she became the first person ever to play a complete concerto (the Beethoven B-flat Major Concerto) at the Worcester Music Festival, the nation's oldest music festival.

Fay moved to Chicago in 1878, where she made her home with her brother Norman. She set up a teaching studio where she promoted the "Deppe Method for the Pianoforte," which she had learned as a student in Germany. Two of her Chicago students later became famous in their own right: John Alden Carpenter, the distinguished American composer, and Almon Kincaid Virgil, piano pedagogue and inventor of the Virgil Clavier, a practice clavier in the form of a small piano having nearly the full compass of the instrument. In 1881 her student memoirs were published and soon achieved a reputation as "the book of the age." The book stimulated many other women musicians to undertake study in Europe so that they too could prepare to enter music as a profession. It remains one of the most durable musical memoirs. In 1883 she developed an innovative concert form, the piano conversation, in which she spoke briefly before each piece she played, discussing what the work was intended to convey and presenting information about the composer. Once she adopted this format, which allowed her to use her verbal as well as her musical skills, the bouts with nervousness that had threatened to undo her as a performer subsided. In striking upon a mode of performing with which she was completely at home--one that not only pleased her but her audiences as well--she had found herself. In Chicago she discovered an outlet for her interest in women's activities by becoming a clubwoman. She helped found the Artists' Concert Club and the Amateur Musical Club, a women's music club. In addition she became a popular lecturer at national meetings of the Music Teachers National Association and a regular contributor of articles on music to the Etude and the Indicator. In the summer of 1885 she had a final reunion with Liszt during her summer travel abroad.

In 1890 she moved to New York City, where she achieved distinction as a pianist, clubwoman, writer, teacher, and advocate for the advancement of musical women in society. Eventually her sister Rose and brother Norman also moved there. In New York she served from 1903 to 1914 as president of the Women's Philharmonic Society of New York, an organization founded in 1899 by her sister Zina Fay Peirce. She remained in New York as a teacher and piano conversationalist through 1916 and retained her residency in New York until 1919. In that year she moved back to Cambridge and took up residence with her brother Norman and sister Rose, both of whom had returned to that city earlier. Eventually her family placed her in a nursing home in nearby Watertown, where she died.

As a woman whose career evolved in the context of a late nineteenth-century American feminism that attempted to widen options for women in political and professional circles, Amy Fay was an important presence in the musical life of the nation. Her decision to go to Germany for music study placed her at the head of a long line of women musicians who, in going abroad for study, dramatically announced to the world that they had the courage to pursue music as a profession rather than as a genteel, female accomplishment that kept idle hands busy. Her advocacy on behalf of musical women through her club work, her writings, and her invention of a concert format uniquely shaped to maximize her gifts for both words and music entitle her to her rightful designation as one of America's notable women.

Bibliography

The Fay Family Papers are in the Schlesinger Library at Radcliffe College and contain many of the unpublished German letters and most of the extant American letters of Amy Fay. The Max Fisch Papers at Texas Tech University contain some information about Amy Fay's older sister and surrogate mother, Zina Fay Peirce.

Of the several editions of Amy Fay's Music Study in Germany in circulation, the 1979 Da Capo edition with preface and index by Edward Downes is particularly valuable. Other important writings by Amy Fay include "The Royal Conservatory of Brussels," Etude 3 (Aug. 1885): 173; "The Amateur Musical Club," Etude 5 (Dec. 1887): 180; "Women and Music," Music 18 (Oct. 1900): 505-7; "Music in New York," Music 19 (Dec. 1901): 179-82; "The Woman Music Teacher in a Large City," Etude 20 (Jan. 1902): 14; and "Some Important Things I Learned in Germany," Etude 29 (Apr. 1911): 227-28.

G. Johnson, One Branch of the Fay Family Tree (1913), contains some background on the Fay family. A chronology of Amy Fay's life may be found in Margaret William McCarthy, "Amy Fay: The American Years," American Music 3 (1985): 52-62. Other sources on Fay's life include works by Margaret William McCarthy: More Letters of Amy Fay: The American Years, 1878-1916 (1986); "Amy Fay's Reunions with Franz Liszt," Journal of the American Liszt Society 24 (1988): 23-32; "Peace through Music: Amy Fay, Grace Spofford, and the International Connection," Komponistinnen Internationales Festival Dokumentation, Women in Music Fifth International Congress 5 (1989): 179-82; and "Feminist Theory in Practice in the Life of Amy Fay," Journal of the International League of Women Composers (Dec. 1991): 9-12. Another related source is L. Nohl's Life of Liszt, translated from the German by G. P. Upton (1884).

Margaret William McCarthy

Back to the top

Citation:

Margaret William McCarthy. "Fay, Amy Muller";

http://www.anb.org/articles/18/18-01863.html;

American National Biography Online Feb. 2000.

Access Date: Fri Aug 09 2013 14:34:31 GMT-0400 (Eastern Standard Time)

Copyright © 2000 American Council of Learned Societies.

Fay, Amy [Amelia] (Muller)

(b Bayou Goula, LA, 21 May 1844; d Watertown, MA, 28 Feb 1928). American pianist and writer on music. She studied in Berlin with Carl Tausig and Theodor Kullak, and was a pupil of Liszt in Weimar. Following her return to the USA in 1875, she settled in Boston, where she earned a reputation as a major concert pianist. In 1878 she moved to Chicago and there achieved national recognition as a lecturer, music critic and teacher; one of her pupils was John Alden Carpenter. In her public appearances, Fay supplemented her playing with brief discussions of the works on the programme. She founded the Artists’ Concert Club and engaged vigorously in the activities of the Amateur Music Club, an organization for women only. She was joined and supported in her commitment to Chicago’s musical life by her sister Rose, the second wife of the conductor Theodore Thomas, and by her brother, Charles Norman, one of the founders of the Chicago SO.

In New York, Fay served from 1903 to 1914 as president of the New York Women’s Philharmonic Society, an organization that promoted effort and achievement by women in the performance, composition, theory and history of music. Her book Music Study in Germany (Chicago, 1880, 2/1896/R1979 with new introduction and index) was also published in England and France, and remains an important source on Liszt. She also contributed articles to the musical press concerning the role and proper recognition of women in the world of music, and published a collection of finger exercises (1889).

Among Fay’s friends were the pianists Paderewski and Fannie Bloomfield Zeisler, the poet Longfellow, and the composer John Knowles Paine. As a performer and teacher Fay helped to widen opportunities for women in the field of music.

Bibliography

A. Fay: Unpublished letters, 1878–1913 (Cambridge, MA, Radcliffe College, Schlesinger Library on the History of Women in America)

W.S.B. Mathews: A Hundred Years of Music in America (Chicago, 1889/R)

G.P. Upton: ‘Music in Chicago’, New England Magazine (Chicago, 1892)

M.W. McCarthy: ‘Amy Fay: the American Years’, American Music, iii/1 (1985), 52–62

M.W. McCarthy, ed.: More Letters of Amy Fay: the American Years, 1879–1916 (Detroit, 1986)

M.W. McCarthy: Amy Fay: America’s Notable Woman of Music (Warren, MI, 1995)

Margaret William McCarthy

Oxford Music Online, accessed 10/17/2017

Amelia Muller Fay (May 21, 1844 – November 9, 1928) was an American concert pianist, manager of the New York Women's Philharmonic Society, and chronicler best known for her memoirs of the European classical music scene.[1] A pupil of Theodor Kullak, Fay traveled to Europe to study with Franz Liszt. Her letters home from Germany, including descriptions of her training and the concerts she attended, were published in 1880 as Music Study in Germany.[2] These memoirs include a comprehensive biographical sketch of Liszt.

Fay was born in 1844 in Bayou Goula, Louisiana. She was the third of six daughters and the fifth of nine children of the Rev. Charles Fay and Emily (Hopkins) Fay of Louisiana and St. Albans, Vermont and Charles Jerome Hopkins's niece. Her sister, Rose Emily Fay, married the conductor Theodore Thomas. Amy Fay studied piano under Professor John Knowles Paine of Harvard and at the New England Conservatory of Music. From 1869 to 1875, she continued her lessons in Germany, where she studied with the most prominent teachers of Europe; pianists Carl Tausig, Theodor Kullak, Franz Liszt, and Ludwig Deppe. Deppe's technique for piano revolutionized her playing and served as the method she herself was to use for her students in the years to come. See: List of music students by teacher: C to F#Amy Fay. On returning to Boston, Fay became well known for her "piano conversations": recitals preceded by short lectures. She moved to Chicago and New York, where she was associated with the Women's Philharmonic Society of New York. She died on November 9, 1928.

wikipedia accessed 10/17/2017

Person TypeIndividual

Last Updated8/7/24

Esens in East Friesland, Germany, 1835 - 1905, Chicago

Boston, 1822 - 1907, Arlington, Massachusetts

Berlin, 1861 - 1935, Medfield, Massachusetts

Burlington, Vermont, 1836 - 1923, Watertown, Massachusetts

Morristown, New Jersey, 1843 - 1923, Washington, DC