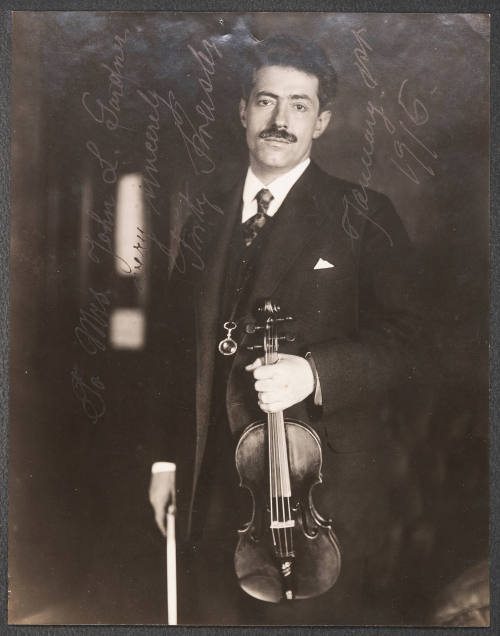

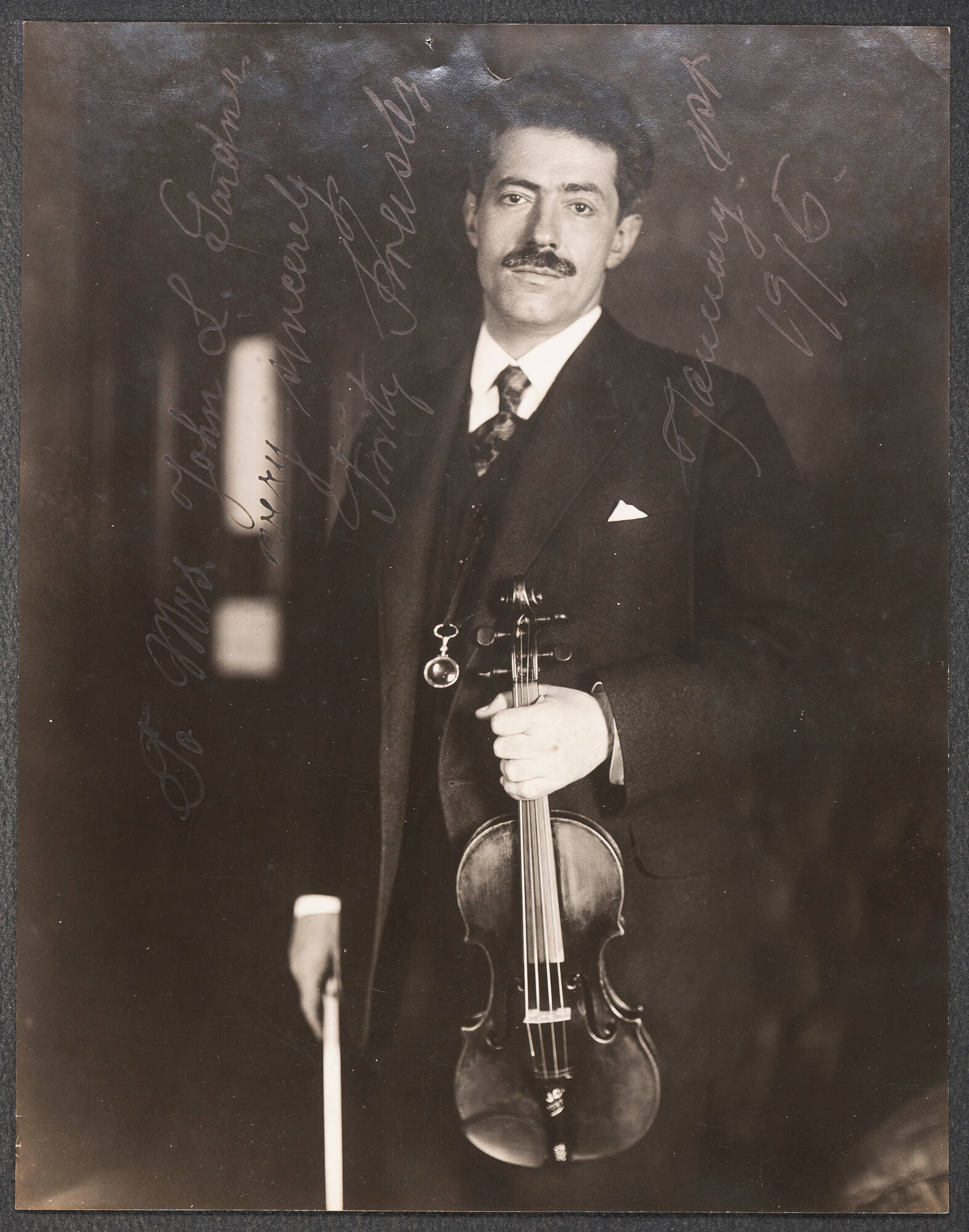

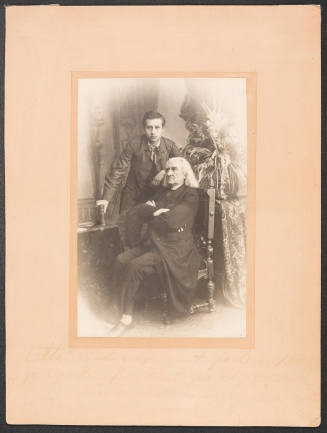

Fritz Kreisler

Vienna, 1875 - 1962, New York

Kreisler, Fritz

(b Vienna, 2 Feb 1875; d New York, 29 Jan 1962). American violinist and composer of Austrian birth. He began to learn the violin at the age of four with his father, a doctor and enthusiastic amateur violinist. After lessons with Jacques Auber, he gained admission to the Musikverein Konservatorium at the age of seven – the youngest child ever to enter. For three years he studied the violin with Joseph Hellmesberger jr and theory with Bruckner. He gave his first performance there when he was nine and won the gold medal when he was ten – an unprecedented distinction. He then studied at the Paris Conservatoire under J.L. Massart, who had taught Wieniawski. Kreisler left the Conservatoire in 1887, sharing the premier prix with four other violinists, all some ten years older. From the age of 12 he had no further violin instruction.

In 1889–90 Kreisler toured the USA as assisting artist to Moriz Rosenthal, but with only moderate success. He returned to Vienna: two years at the Gymnasium and two as a pre-medical student were followed by military service. All this time, Kreisler barely touched the violin. However, once he decided on a musical career, he quickly regained his technique. In 1896 he applied to join the orchestra of the Vienna Hofoper but failed, allegedly because of poor sightreading. Two years later he had the satisfaction of scoring a notable success with the Vienna PO, actually the same ensemble that had denied him a place. A year later, on December 1899, his début with the Berlin Philharmonic under Nikisch marked the beginning of an international career. He reappeared in the USA during the 1900–01 season, then made his London début at a Philharmonic concert under Richter on 12 May 1902. In 1904 he was presented with the Philharmonic Society’s gold medal. Elgar composed his Violin Concerto for Kreisler who gave its première on 10 November 1910 at Queen’s Hall, with Elgar conducting.

At the outbreak of World War I Kreisler joined the Austrian Army. He was medically discharged after being wounded, and embarked for the USA (his wife’s native country) in November 1914. However, anti-German feelings ran so high that he withdrew from the platform, reappearing in New York on 27 October 1919. From 1924 to 1934 he lived in Berlin. When Austria was annexed by the Nazis the French Government offered him citizenship. In 1939 he returned for good to the USA, and became an American citizen in 1943. A traffic accident in 1941 impaired his hearing and eyesight; nevertheless, he resumed his career. He made his last Carnegie Hall appearance on 1 November 1947, though he broadcast during the 1949–50 season. After that, his interest in the violin waned; he sold his collection of instruments and kept only an 1860 Vuillaume.

Kreisler was unique. Without exertion (he practised little) he achieved a seemingly effortless perfection. There was never any conscious technical display. The elegance of his bowing, the grace and charm of his phrasing, the vitality and boldness of his rhythm, and above all his tone of indescribable sweetness and expressiveness were marvelled at. Though not very large, his tone had unequalled carrying power because his bow applied just enough pressure without suppressing the natural vibrations of the strings. The matchless colour was achieved by vibrato in the style of Wieniawski who (in Kreisler’s words) ‘intensified the vibrato and brought it to heights never before achieved, so that it became known as the “French vibrato”’. However, Kreisler applied vibrato not only on sustained notes but also in faster passages which lost all dryness under his magic touch. His methods of bowing and fingering were equally personal. In fact his individual style was, as Flesch said, ahead of his time, and may explain his comparatively slow rise to fame. Yet there is hardly a violinist in the 20th century who has not acknowledged admiration of and indebtedness to Kreisler.

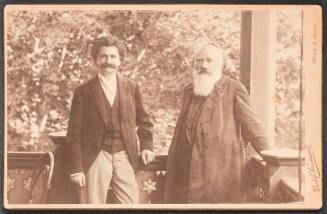

Kreisler was also a gifted composer. Among his original works are a string quartet, an operetta, Apple Blossoms (with Viktor Jacobi, 1919), cadenzas to the Beethoven and Brahms concertos, and numerous short pieces (Tambourin chinois, Caprice viennois etc.). He made many transcriptions and editions. In addition, he composed dozens of pieces in the ‘olden style’ which he ascribed to various 18th-century composers, such as Pugnani, Francoeur, Padre Martini etc. When Kreisler admitted in 1935 that these pieces were a hoax, many critics (including Ernest Newman) were indignant while others accepted it as a joke. It is strange indeed that so many experts were misled by Kreisler’s impersonations; at any rate, these charming pieces continue to enrich the violin repertory.

Writings

Four Weeks in the Trenches (Boston and New York, 1915)

Bibliography

CampbellGV

SchwarzGM

L.P. Lochner: Fritz Kreisler (New York, 1950/R) [with discography and repr. of the controversy with Newman]

F. Bonavia: ‘Fritz Kreisler’, MT, ciii (1962), 179

J.W. Hartnack: Grosse Geiger unserer Zeit (Munich, 1967, 4/1993)

J. Creighton: Discopaedia of the Violin, 1889–1971 (Toronto, 1974)

I. Yampol?sky: Frits Kreysler: zhizn? i tvorchestvo (Moscow, 1975)

The Strad, xcviii (1987) [Kreisler edition]

A.C. Bell: Fritz Kreisler Remembered: a Tribute (Braunton, 1992)

H. Adamson: ‘Forgotten Treasure’, The Strad, cvii (1996), 692–3

Boris Schwarz

Source: Grove Music Online accessed 10/20/2017

Person TypeIndividual

Last Updated8/7/24

New Malden, Kingston-upon-Thames, England, 1873 - 1951, Miami, Florida

Bethel, Missouri, 1854 - 1926, Rumford Falls, Maine

Kharkov, Ukraine, 1863 - 1945, New York

Bonn, Germany, 1770 - 1827, Vienna

Hamburg, Germany, 1809 - 1847, Leipzig, Germany