Image Not Available

for Arthur Waley

Arthur Waley

Royal Tunbridge Wells, 1889 - 1966, London

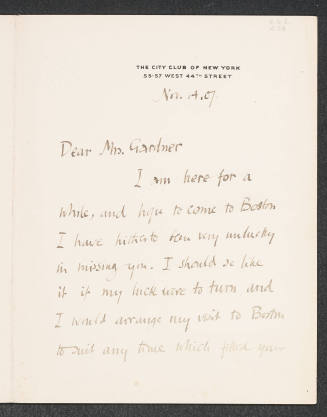

Waley [formerly Schloss], Arthur David (1889–1966), translator of Chinese and Japanese literature, was born at Tunbridge Wells on 19 August 1889, the second of the three sons of David Frederick Schloss (1850–1912), economist and Fabian socialist, and his wife, Rachel Sophia, daughter of Jacob Waley, legal writer and professor of political economy. His elder brother was Sir (Sigismund) David Waley, authority on international finance. The family adopted Jacob Waley's surname in 1914, in what is assumed to have been a response to anti-German sentiment at the onset of the First World War.

Arthur Waley was brought up in Wimbledon and sent to Rugby School (1903–6), where he shone as a classical scholar and won an open scholarship at King's College, Cambridge, while still under seventeen. He spent a year in France before going up to the university in 1907; he obtained a first class in part one of the classical tripos in 1910 but had to abandon Cambridge when he developed diminished sight in one eye. He rested, and travelled on the continent, becoming fluent in Spanish and German.

Although Waley had got to know Sydney Cockerell at Cambridge, it was through Oswald Sickert, a brother of the painter, that he was led to consider a career in the British Museum. Sickert was one of a group of friends, mostly museum staff or researchers in the library, who met regularly for lunch in the years before 1914 at the Vienna Café in New Oxford Street; Laurence Binyon was also one of the regulars. In June 1913, supported by Sickert and Cockerell, Waley started working in the newly formed sub-department of oriental prints and drawings under its first head, Binyon. His task was to make a rational index of the Chinese and Japanese painters represented in the museum collection; he immediately started to teach himself Chinese and Japanese. He had no formal instruction, but by 1916 was privately printing his first fifty-two translations of Chinese poems, and in 1917–18 he added others in the first numbers of the Bulletin of the newly established School of Oriental Studies, and in the New Statesman and the Little Review. By 1918 he had completed enough translations of poems, mainly by writers of the classic Tang period, to have a volume entitled A Hundred and Seventy Chinese Poems accepted for publication, largely on account of a perceptive review in the Times Literary Supplement of the 1917 Bulletin poems. In 1919 Stanley Unwin became his publisher and remained his constant friend and admirer.

From his sixteen years at the museum Waley's only official publications were the index of Chinese artists (1922), the first in the West; and a catalogue (1931) of the paintings recovered from Tunhuang (Dunhuang) by Sir Aurel Stein and subsequently divided between the government of India and the British Museum. An Introduction to the Study of Chinese Painting (1923) was a by-product of his unpublished notes on the national collection and its relation to the great tradition of Chinese painting. He also set in order and described the museum's Japanese books with woodcut illustrations and its large collection of Japanese paintings. He retired from the museum on the last day of 1929 because he had been told that he ought to spend his winters abroad. Waley had started to ski as early as 1911 and liked to get away into the mountains whenever he could, generally to Austria or Norway and not to the regular runs but as a lone figure on the high snow slopes.

Waley's largest translation, and probably the one for which he was best-known during his lifetime, was of the Genji Monogatari by Murasaki Shikibu, the late tenth-century classical novelist of Japan. The first volume appeared in 1925; the sixth volume did not appear until 1933. This was not the first of Waley's Japanese translations, for it had been preceded by two volumes of classic poetry, selections from the Uta (1919) and No plays (1921). In these he was more concerned with the resonances of the Japanese language, whereas in the Genji he aimed rather at an interpretation of the sensibility and wit of the closed society of the Heian court, voiced in the idiomatic English of his day. Inevitably this shows signs of dating as the idiom itself becomes remote, and a less exuberant version (by Edward G. Seidensticker, 1976) took its place.

Waley continued through life as a creative translator of Chinese poetry. His use of ‘sprung rhythm’ to convey in the English mode the shape of Chinese verse forms differs from that of Gerard Manley Hopkins: in place of urgent acceleration it evokes the clear phrasing of the flute, an instrument he liked to play. But Waley's systematic engagement with China over the last thirty years of his life took him far beyond poetry. He revisited the early thinkers (The Way and its Power, 1934; The Analects of Confucius, 1938; Three Ways of Thought in Ancient China, 1939), explored the lives of sympathetic writers and divines (Bo Juyi, 1949; Li Bo, 1950; The Real Tripitaka, 1952; Yuan Mei, 1956), and discovered the bright colours of vernacular literature (Monkey, 1942; Ballads and Stories from Tunhuang, 1960). These books all speak with the same clear but intimate voice; their readers find that a distant and alien world grows subtly close to their own.

Waley moved with the smooth grace of the skier, his gesture was courtly in salutation, but more characteristic was the attentive, withdrawn pose of his finely profiled head with its sensitive but severe mouth. His voice was high-pitched but quiet and unchanging, so as to seem conversational in a lecture, academic in conversation. In later life he had a slight stoop which accentuated his ascetic appearance. He enjoyed meeting sympathetic people and hearing their conversation but never spoke himself unless he had something to say; he expected the same restraint in others. His forty years' attachment to Beryl de Zoete (d. 1962), anthropologist and interpreter of Eastern dance forms, brought out the depth of feeling and tenderness of which he was capable.

As a scholar Waley aimed always to express Chinese and Japanese thought and sensibility at their most profound levels, with the highest standard of accuracy of meaning, in a way that would not be possible again because of the growth of professional specialization. He was always a lone figure in his work, though he was not remote from the mood of his times. Although he never travelled to east Asia and did not seek to confront the contemporary societies of China or Japan, he was scathingly critical of the attitude to their great cultures displayed by the West in the world in which he grew up: hence his scorn for the older generation of Sinologists and his hatred of imperialism, as shown in The Opium War through Chinese Eyes (1958).

For over forty years Waley lived in Bloomsbury, mostly in Gordon Square. Although he had many connections with the Bloomsbury group of artists and writers, he was never a member of a clique, and his friendships with the Stracheys, the Keyneses, and with Roger Fry dated from his Cambridge days. He was elected an honorary fellow of King's in 1945 but was not often seen there. Other honours also came to him late: election to the British Academy in 1945, the queen's medal for poetry in 1953, CBE in 1952, and CH in 1956. Aberdeen and Oxford universities awarded him honorary doctorates. After Beryl de Zoete's death in 1962 he went to live in Highgate where he was looked after by Alison Grant Robinson, an old friend from New Zealand, who was formerly married to Hugh Ferguson Robinson. He married her a month before his death at his home, 50 Southwood Lane, Highgate, from cancer of the spine on 27 June 1966.

A volume of appreciation and an anthology of Waley's writings was edited by Ivan Morris, under the title Madly Singing in the Mountains (1970), a phrase taken from a poem by Bo Juyi which Waley had translated in 1917 and chosen because of its ‘joyfulness’. For Waley the work of a translator was ‘made to the measure of his own tastes and sensibilities’ (I. Morris, ed., Madly Singing in the Mountains, 1970, 158). He sought to make his translations works of art, aiming at literature rather than philology. In this he was successful.

Basil Gray, rev. Glen Dudbridge

Sources

A. D. Waley, introduction, A hundred and seventy Chinese poems, new edn (1962) · I. Morris, ed., Madly singing in the mountains (1970) · The Times (28 June 1966) · L. P. Wilkinson, King's College Annual Report (1966) · personal knowledge (1981) · private information (1981) · A. Waley, A half of two lives (1982)

Archives

King's AC Cam., papers and family papers relating to him; further papers · Rutgers University, New Brunswick, corresp., literary MSS, and papers :: Dartington Hall, Totnes, letters to Leonard Elmhirst · Harvard University, Center for Italian Renaissance Studies, near Florence, Italy, letters to Bernard Berenson · McMaster University, Hamilton, Ontario, corresp. with Bertrand Russell

SOUND

BL NSA, ‘Conversation’, P76R BD1, P114R BD1 · BL NSA, ‘He never went to China’, T2409W C1 · BL NSA, ‘Hunter of beautiful words’, B1610/1 · BL NSA, performance recordings

Likenesses

R. Whistler, pencil drawing, c.1928–1938, NPG [see illus.] · W. Stoneman, photograph, 1946, NPG · C. Beaton, photograph, 1956, NPG · M. Ayrton, pencil drawing, 1957, King's Cam. · R. Strachey, oils, NPG

Wealth at death

£152,998: administration, 1966, CGPLA Eng. & Wales

© Oxford University Press 2004–16

All rights reserved: see legal notice Oxford University Press

Basil Gray, ‘Waley , Arthur David (1889–1966)’, rev. Glen Dudbridge, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn, Jan 2011 [http://proxy.bostonathenaeum.org:2055/view/article/36683, accessed 24 Oct 2017]

Arthur David Waley (1889–1966): doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/36683

Person TypeIndividual

Last Updated8/7/24

Salem, Massachusetts, 1853 - 1908, London

Lefkas Island, Greece, 1850 - 1904, Tokyo

Bishopbriggs, 1818 - 1878, Venice

Geneva, 1826 - 1897, London