Horace Gray

Boston, 1828 - 1902, Nahant, Massachusetts

After further preparation in the firm of Sohier and Welch and then with John Lowell, Gray was admitted to the bar in 1851. A short time later Luther S. Cushing, clerk of the supreme court of judicature, fell seriously ill, and Gray assumed his duties on a temporary basis. The office became Gray's permanently when Cushing died in 1854. The position was ranked only slightly below a judgeship, and its duties were well suited both to Gray's talents and proclivities. In particular, his extensive case notes reflected his search for historical truth as a basis for legal precedent. His notes on the writs of assistance question of 1761, in which James Otis had successfully argued against the royal government's use of general search warrants, and on slavery in the Commonwealth proved of value to his contemporaries and also to modern scholars, who have built on his thorough scholarship.

Besides his clerkship, Gray honed his skill as an advocate with the elite of the highly regarded Boston bar, which included Benjamin R. Curtis after Curtis's resignation from the U.S. Supreme Court in 1857. Gray's partners included Ebenezer Rockwood Hoar, future supreme judicial court justice and attorney general under President Ulysses S. Grant. Fully devoted to the law, Gray had little time for politics. Like his partner Hoar, however, he gravitated from "Conscience" Whig to Free Soiler to Republican. His opposition to slavery is further indicated in an attack, coauthored with John Lowell, Jr., on Chief Justice Roger B. Taney's Dred Scott opinion. Typically, the critique was solidly based on legal rather than political grounds. With the outbreak of the Civil War, Gray rendered significant legal advice to Republican governor John A. Andrew, although his support for the war was tempered by constitutional scruples over Abraham Lincoln's Emancipation Proclamation.

In 1864 Governor Andrew appointed Gray to the supreme judicial court, and in 1873, upon the death of Chief Justice Reuben Chapman, Gray succeeded to the chief justiceship. The court's heavy caseload involved its members as both trial and appellate judges. Opinions differed on Gray's courtroom demeanor and the extent to which his rigor was mitigated by kindness, but recognition of his capacity for work was unanimous. As chief justice he even proofread the court reports. In seventeen years on the Massachusetts court, Gray spoke for it 1,367 times. Moreover, the number of his opinions increased markedly once he became chief justice, as he seldom delivered less than a quarter of the seven-judge court's opinions each term. Remarkably, he dissented only once in seventeen years, an indication of his institutional commitment.

Gray's first opinion on the court was in a case involving ownership of a heifer. He expended five pages in notes, signaling that he was not changing his habits from his reporter days. Indeed, he contributed a number of essays on several points of law, ranging from ocean flats to the role of trustees in inheritance cases. He contributed to the court's assumption of more equity cases, as he was one of the few judges in the country with a mastery of the subject. Unnoticed at the time, Gray hired promising Harvard Law School graduates as clerks, a custom he continued on the U.S. Supreme Court. That practice became institutionalized on the Supreme Court when his successor, Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr., maintained it. As one of Gray's early clerks, the brilliant Louis D. Brandeis demonstrated Gray's commitment to ability, and their working relationship served as a model for later clerks.

It was traditional in the nineteenth century for Supreme Court justices to be appointed from a particular circuit's most prominent state, which in the First Circuit was Massachusetts. In 1881, with the occupant of the First Circuit seat, Nathan Clifford of Maine, in his dotage and Republicans in control of the Senate and the presidency, Gray seemed certain to be appointed. The previous, image-conscious Rutherford B. Hayes administration had consulted Gray, though he was not a partisan, on Massachusetts patronage matters. To make the appointment unanimous, the Supreme Court justices informed President Chester Arthur, who made the appointment following James A. Garfield's assassination, that they favored Gray. He had come from being a lawyers' lawyer to being a judges' judge, and he took his seat on 9 January 1882.

Gray's twenty years on the Court are not easily categorized. Continuing a number of his career traits, his opinions often took the form of legal essays, he worked overtime to eliminate disharmony on the Court, and he maintained his penchant for precedent unabated. The image that emerges is the ultimate team player on the Morrison R. Waite Court and the Melville Weston Fuller Court. Gray was the recognized historical scholar on the bench who could be counted on to do more than his share of the task. He worked closely with Fuller in securing passage of the Circuit Court of Appeals Act of 1891. The closeness of the brethren is indicated by Gray's marriage in 1889 to Jane Matthews, the daughter of his late colleague Stanley Matthews. The couple had no children. Gray had adhered to the doctrine of sovereign immunity, that government cannot be sued, as a Massachusetts judge, and he expounded it in his dissent in United States v. Lee (1882), in which Robert E. Lee's heirs sued for the return of the family's estate confiscated during the Civil War. In general Gray supported the strengthened Union that had emerged from the Civil War. Thus in Juilliard v. Greenman (1884), his opinion for the Court sustained Congress's power to issue greenbacks (paper money), for which he was castigated by friends, even in their memorial tributes to him. Gray's commitment to precedent, or closely following prior decisions, explains his dissent along with Waite in the Wabash case (1886), in which the Court's decision overruled the Granger cases (1877) that had sustained state regulation of railroads. But Gray's adherence to governmental exercise of power and to following precedents was tempered by his conservatism. He frequently aligned with two of the most conservative members of the Fuller Court, and he joined the hysteria-driven 5 to 4 decision invalidating a congressional income tax in Pollock v. United States (1895). Perhaps Gray's best-known opinion was in United States v. Wong Kim Ark (1898), in which he ruled that a person born to Chinese parents in the United States was a citizen who could not be excluded from returning to the country after a visit to China. Gray, however, had found grounds for not extending citizenship to a Native-American claimant in Elk v. Wilkins (1884) and joined his colleagues, with the exception of John Marshall Harlan, in what historian John Hope Franklin has called "the betrayal of the Negro" in the Civil Rights cases (1883), which invalidated the Civil Rights Act of 1875. In short, his record on equality for racial minorities under the Constitution was mixed.

A robust outdoorsman, Gray was six feet four inches tall and might be imagined in pursuit of an elusive hermit thrush. He enjoyed generally good health until his last years on the bench, which culminated in a stroke on 3 February 1902. To avoid burdening the Court, he resigned in July of that year, to take effect upon the appointment of a successor. He died in Nahant, Massachusetts.

George F. Hoar, one of Gray's classmates at Harvard Law School, had as a senator pushed for Gray's Supreme Court appointment. Hoar perhaps summed up Gray's career best: "In the first place, Judge Gray was a good lawyer. He did not make mistakes. In the second place, his devotion to his profession was like that of a holy priest to his religion." But Hoar also noted, "I think Judge Gray's fame . . . would have been greater . . . if he had resisted sometimes the temptation to marshal an array of cases, and had suffered his judgments to stand on his statement of legal principles without the authorities" (p. 165). It has been noted that Christopher Columbus Langdell, a law school classmate of Gray's, succeeded in formulating legal education the way that Gray applied law as a judge--laying out precedent in historical sequence within specific categories to demonstrate particular rules, or legal formalism.

Bibliography

A useful capsule summary is Louis Filler, "Horace Gray," in The Justices of the United States Supreme Court, 1789-1978, ed. Leon Friedman and Fred L. Israel (1978). Also see Robert M. Spector, "Legal Historian on the United States Supreme Court: Justice Horace Gray, Jr., and the Historical Method," American Journal of Legal History 12 (July 1968): 181-210. A full-length work is Stephen R. Mitchell, "Mr. Justice Gray" (Ph.D. diss., Univ. of Wisconsin, 1961). The best of the contemporary evaluations is George F. Hoar, "Memoir of Horace Gray," Proceedings of the Massachusetts Historical Society 18 (1905). Gray is in Mark DeWolfe Howe, Justice Holmes: The Proving Years 1870-1882, chap. 4 (1963). Holmes followed Gray on both the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court and the Supreme Court.

Donald M. Roper

Back to the top

Citation:

Donald M. Roper. "Gray, Horace";

http://www.anb.org/articles/11/11-00347.html;

American National Biography Online Feb. 2000.

Access Date: Fri Aug 09 2013 15:09:50 GMT-0400 (Eastern Standard Time)

Copyright © 2000 American Council of Learned Societies.

Person TypeIndividual

Last Updated8/7/24

Brighton, Massachusetts, 1839 - 1915, Boston

Beverly, Massachusetts, 1851 - 1930, Beverly, Massachusetts

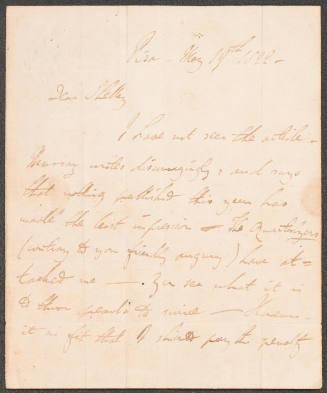

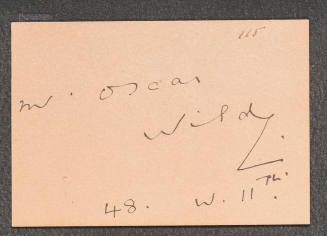

Horsham, 1792 - 1822, near Viareggio

Hampstead, 1811 - 1856, Boulogne

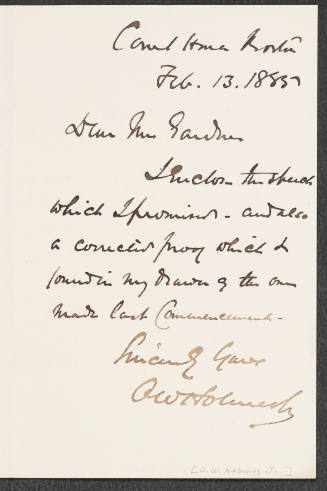

Boston, 1841 - 1935, Washington, D.C.

Auchlunies, 1825 - 1916, Brighton