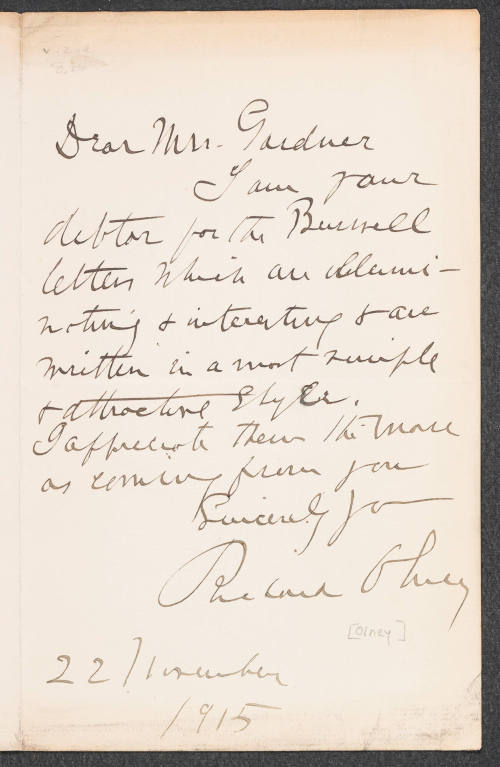

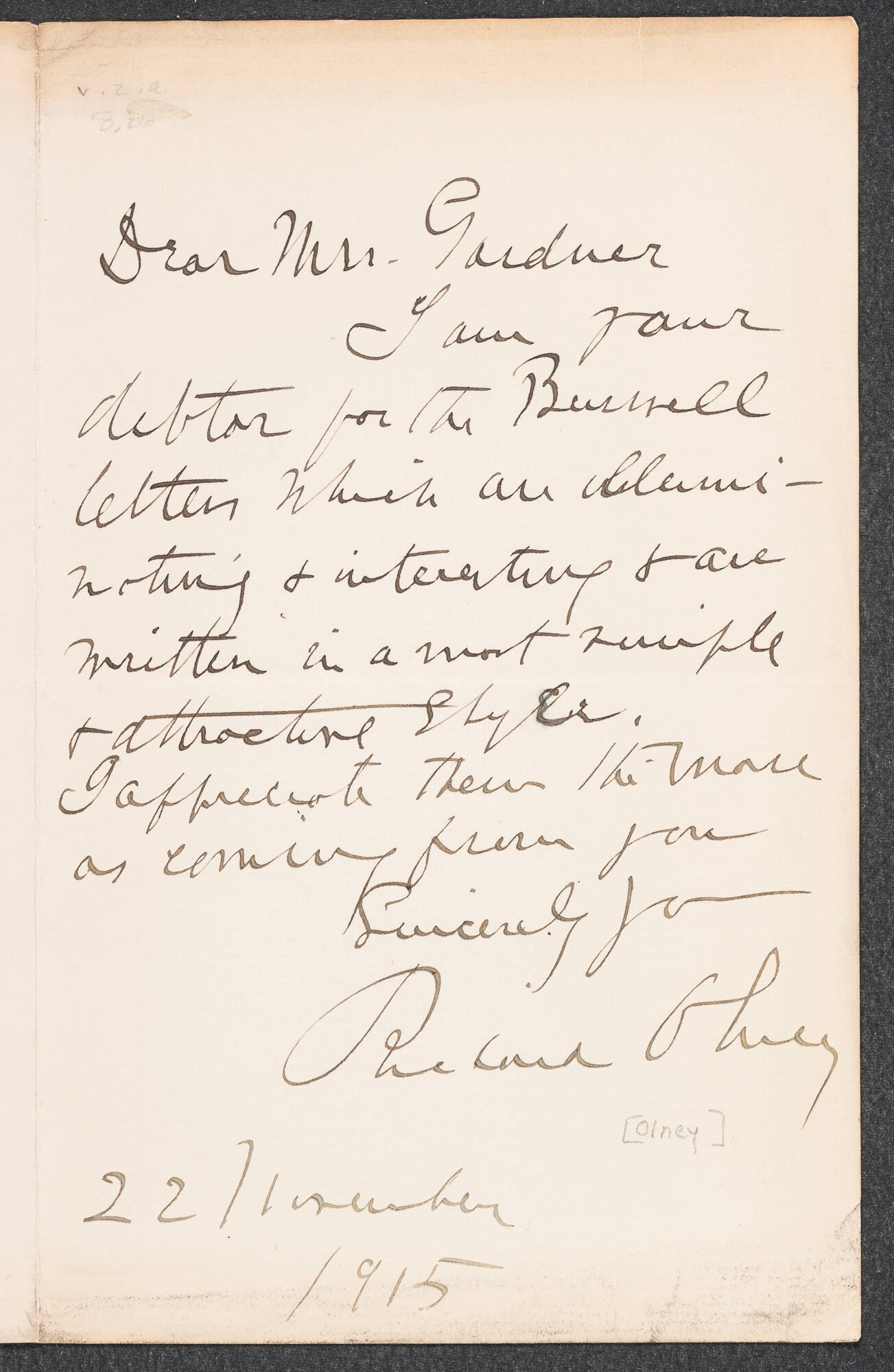

Richard Olney

Oxford, Massachusetts, 1835 - 1917, Boston

Olney was educated at Brown College, 1851-1856, and Harvard Law School, 1856-1858. He was admitted to the bar of Suffolk County in April 1859 and found his first employment with Judge Benjamin F. Thomas of Boston. Within two years he married the judge's daughter Agnes (6 Mar. 1861), and on Thomas's death in 1876, he inherited the judge's practice. The Olneys had two children.

At first Olney specialized as his father-in-law had in wills and trust estates. Although not especially lucrative, the practice brought him into contact with leading Brahmin families, the so-called "proper Bostonians." Increasingly, these clients entrusted him with their business affairs. Between 1876 and 1879 Olney successfully reorganized the financially distressed Eastern Railroad Company of Massachusetts. In the process he became the firm's general counsel and a member of its board of directors. In 1884, when the Boston & Maine Railroad leased the Eastern, Olney became that company's attorney and moved to its board of directors. His work there centered on legal problems involved in forging the firm's near monopoly over rail traffic in northern New England. Success in that venture made Olney one of Boston's leading railroad lawyers.

After 1886 Boston interests in control of the Chicago, Burlington & Quincy Railroad began turning to Olney for advice. In 1889 he became that line's general counsel and a member of its board. For the most part, his efforts were aimed at thwarting "Granger laws" (state measures for regulating railroads and their rates) and later the federal Interstate Commerce Act.

In appointing the cabinet for his second term (1893-1897), President Grover Cleveland selected Olney as attorney general. The Boston lawyer's only previous excursions into politics had been a one-year term in the Massachusetts legislature in 1874 and an unsuccessful bid for the state's attorney generalship in 1876. Unlike his colleagues, Olney prepared for cabinet meetings by looking into any important matter likely to arise, not just those related to his own department. As a consequence, he soon became all but indispensable to the president.

Olney played a significant role in almost every major issue of the second Cleveland administration. He argued against both the annexation of Hawaii and using force to restore Queen Liliuokalani to her throne; he worked for repeal of the Sherman Silver Purchase Act; he urged American neutrality in the Cuban struggle for independence from Spain; and he used federal court injunctions backed by the army to halt the march of Jacob S. Coxey's armies of the unemployed on Washington in 1894.

His most celebrated and controversial act as attorney general was suppressing the Chicago railroad boycott and strike of 1894 (better known as the Pullman strike). The affair began as a sympathetic boycott in support of a strike by American Railway Union (ARU) affiliates at the Pullman Company near Chicago. The ARU boycotted all Pullman sleeping cars on the nation's railroads. The major railroad companies centered in Chicago, already organized in the General Managers' Association (GMA), agreed to discharge any employee who boycotted sleeping cars. The ARU in turn struck every railroad that discharged one of its members. Within days railroad traffic in the area and across much of the nation was brought to a standstill. Olney forcefully moved against the boycott-strike. On advice of the GMA, he named a Chicago railroad lawyer to represent the Justice Department in Chicago. He ordered all U.S. attorneys and marshals to protect the movement of trains carrying mail or interstate commerce. He authorized the special attorney in Chicago to seek a blanket injunction against Eugene V. Debs, president of the ARU, and "all other persons whomsoever," forbidding them from aiding, abetting, encouraging, or promoting the strike in any way. When those measures failed, Olney advised Cleveland that nothing remained but for the president to call out the army to enforce the injunction. Illinois governor John Peter Altgeld protested that this action unconstitutionally infringed on the sovereignty of Illinois. Cleveland, allegedly working from a draft prepared by Olney, replied tersely that he was enforcing federal law and that Illinois was part of the United States.

It was not generally known at the time, but Olney was involved in a serious conflict of interest. Until the end of the strike he continued to receive his regular salary, an amount greater than what he was paid as attorney general, for services rendered as general counsel of the Burlington, one of the railroads directly involved in the strike. When the issue was raised, he quietly stopped the salary but continued as the line's general counsel. It is unlikely, however, that the source of his private income determined his conduct during the strike: his whole professional career had been on the side of large corporations and railroads. Nonetheless, even in that era he was guilty of a breach of ethics, if not of law.

During Olney's tenure as attorney general, the Justice Department brought three major cases before the U.S. Supreme Court. Olney regarded In re Debs, growing out of the Pullman strike, as the most important and personally argued that case before the high court. A sweeping unanimous decision, based largely on Olney's brief, upheld the blanket injunction and in effect outlawed strikes against railroads carrying either interstate commerce or the mail for the next quarter-century.

In United States v. E. C. Knight et al. (the sugar trust case), the Court so narrowly construed the Sherman Antitrust Act as to render it useless against trusts for at least a decade. Olney advanced the case, fully expecting the Court to invalidate the law, which he thought was worthless. In a similarly restrictive interpretation of the Constitution, the Court in Pollock v. Farmers' Loan & Trust Company struck down the income tax, closing off that source of revenue until adoption of the Sixteenth Amendment in 1913. As the government's advocate, Olney regarded the case as very important and hated losing, but, as he said, he took comfort in not himself having to file a return.

Upon the death of Secretary of State Walter Q. Gresham in 1895, Cleveland promoted Olney to that post. Neither Olney's manner nor his temperament was well suited to the norms of international diplomacy. He issued ultimatums and made demands on sovereign nations much as if they were opponents in litigation. He told the Spanish minister that if a frequently deferred claim of the United States was not paid, he would urge the president to lay the matter before Congress, implying that a resort to force might follow.

Most notorious was his similar ultimatum to Great Britain demanding submission of the long-standing boundary dispute between British Guiana and Venezuela to arbitration by the United States. Charging that Britain's claim violated the Monroe Doctrine, he asserted that the "infinite resources" and "isolated position" of the United States rendered it "master of the situation and practically invulnerable as against any or all other powers." When the deadline for replying passed, Olney helped Cleveland draft a message to Congress, asking for authority to draw the proper boundary line and if necessary to use armed force to uphold it. Britain subsequently accepted arbitration, and the war fever precipitated by the message died down. Although his initiation of the crisis needlessly risked war, his subsequent handling of the affair contributed to a reasonable settlement.

Twice Olney's admirers unsuccessfully urged his candidacy for the presidency, first in 1896, again in 1904. Those favoring him were never numerous, and he regarded office-seeking as unseemly. Further, Cleveland's coy handling of a possible third term in 1896 blocked all conservative Democratic candidates until too late to halt William Jennings Bryan's steamroller. After two failed bids by Bryan, too few remembered Olney, who by 1904 was sixty-nine years old.

In his postcabinet years, Olney occasionally wrote or spoke on foreign policy and labor topics. For the most part, however, he practiced law until his retirement in 1908. In 1913 President Woodrow Wilson offered him appointments as ambassador to Great Britain and membership on the Federal Reserve Board, both of which he declined. He died in Boston.

Bibliography

The bulk of Olney's personal papers are in the Richard Olney Papers, and important correspondence with the president is in the Grover Cleveland Papers, both in the Manuscript Division of the Library of Congress. Professional correspondence is in the Olney and Charles E. Perkins collections, Burlington Railroad Archives, Newberry Library, Chicago. Official correspondence and records are in the files of the Justice and State departments at the National Archives. Articles published by Olney include "International Isolation of the United States," Atlantic Monthly 81 (May 1898): 577-88; "Growth of Our Foreign Policy," Atlantic Monthly 85 (Mar. 1900): 289-301; "Recent Phases of the Monroe Doctrine," Boston Herald, 1 Mar. 1903; "Discrimination Against Union Labor--Legal?" American Law Review 42 (Mar.-Apr. 1908): 161-67; and "National Judiciary and Big Business," Boston Herald, 24 Sept. 1911. There are two biographies: Henry James, Richard Olney and His Public Service (1923), and Gerald G. Eggert, Richard Olney: Evolution of a Statesman (1974). An obituary is in the Boston Globe, 10 Apr. 1917.

Gerald G. Eggert

Back to the top

Citation:

Gerald G. Eggert. "Olney, Richard";

http://www.anb.org/articles/05/05-00577.html;

American National Biography Online Feb. 2000.

Access Date: Tue Aug 06 2013 12:36:44 GMT-0400 (Eastern Standard Time)

Copyright © 2000 American Council of Learned Societies.

Person TypeIndividual

Last Updated8/7/24

Salem, Massachusetts, 1860 - 1936, Squam Lake, New Hampshire

Cincinnati, 1857 - 1930, Washington, D.C.

Salem, Indiana, 1838 - 1905, Lake Sunapee, New Hampshire

Cincinnati, 1840 - 1907, Westwood, Massachusetts

Beverly, Massachusetts, 1851 - 1930, Beverly, Massachusetts

Boston, 1831 - 1920, Boston

Westminster, Massachusetts, 1839 - 1925, Washington, D.C.