George R. Parkin

Salisbury, New Brunswick, Canada, 1846 - 1922, London

Education and early career

Parkin recalled his parents' ‘hand to hand struggle with the forest and soil’—a life striking for its ‘bareness’, with ‘little music, few books, [and] not much polished society’. His mother gave him a love of literature, however, and young George attended school whenever time could be ‘snatched from the hoeing of potatoes, making hay, [or] chopping wood’. These early glimmers of a distant world of learning awakened

a burning desire to know and a longing to see with my own eyes the places one read about, to meet men who wrote books or did things, to get in touch with the world of which the faint echoes only came to one's country life. (National Archives of Canada, George R. Parkin and Annie Parkin MSS, ‘Social problems’, 24597; autobiographical fragment, 37594)

Parkin followed this desire first to the normal school at Saint John, New Brunswick (1862–3), where he received rudimentary training as a teacher, and then to positions in rural primary schools at Buctouche and Campobello Island. He attended the University of New Brunswick in Fredericton (1864–7), where he imbibed the liberal gospel of mid-Victorian progress and optimism from Macaulay and through the direction of his professors. He was accepted into Fredericton society, thereby acquiring the social skills he would need in later life. After graduating magna cum laude and gold medallist, he taught at the Gloucester county grammar school in Bathurst (1867–71) before his appointment as principal/headmaster of the Fredericton Collegiate (1872–89).

Parkin formed in these years his lifelong conviction, expressed in his normal school notebook, that ‘the degree of civilization attained by any nation’ is a direct result of its standard of education, and that the teacher has enormous power by forming ‘the morals and manners of those ... whose influence for good or bad will be extensively felt’ (Parkin MSS, 25619–25620). This belief underpinned his later work not only in education, but also in his public campaigns for imperial unity, social regeneration, and Christian responsibility. He honed his effective public-speaking techniques in a series of local lectures on temperance, education, democracy, history, and imperial unity. Yet these were troubled years for Parkin. His careful reading of Carlyle challenged the liberal notions of his university days, and his close friendship with John Medley, the high-church Anglican bishop of Fredericton, undermined the individualistic evangelical Baptist faith of his youth for a more learned, collective approach to religion. Not knowing which way to turn to reconcile his conflicting liberalism and conservatism, or his evangelicalism and high Anglicanism, he suffered a severe identity crisis and nervous breakdown. Medley stepped into the breach and sponsored Parkin for a year at Oxford University in 1873–4.

This year set the direction for Parkin's life. As an older student with considerable experience in public speaking he was a great success at the Oxford Union, and was accorded the unusual honour for a non-degree freshman of being elected its secretary. In a famous debate he defeated H. H. Asquith over the issue of imperial unity, when he affirmed its desirability against the then widespread prevalence of Little Englandism. The resultant acclaim solidified his earlier belief in a united British empire as a force for good in the world. During his Oxford year he was also deeply impressed by Edward Thring, headmaster of Uppingham, and saw in Thring's ideals for the English public school a necessary corrective to the lower standards of pioneer schools in Canada. Thring was equally charmed, and after many years of friendship assigned Parkin the task of writing his biography (published in 1898).

Parkin was attracted to the idealism that animated much late nineteenth-century British and Canadian life. He absorbed this from Thring as well as from personal contacts with the brilliant circle at Balliol College, including Benjamin Jowett, T. H. Green, and Lewis Nettleship, and from John Ruskin, who gave influential lectures that year. Parkin accepted idealism, as did many of his fellow students, as a practical creed rather than a philosophical system, a belief that a moral community in the world would result from the ethical character of citizens moved by a sense of selfless public service rather than by a desire for material gain or demagogic approval. In idealism (and in the related National Church movement to which he was also drawn), Parkin found a resolution of his identity crisis. His evangelical energy was rechannelled into a lifelong mission to promote the central tenets of Christian idealism in the empire, school, church, and society.

Parkin spent the next fifteen years teaching in Fredericton. He tried in his own school, and in a connected residential establishment he founded, to implement Thring's concept of building citizenship through the regimen of residential school life and a classical education under a committed headmaster. These initial experiments were not successful. While disappointed, Parkin remained a master teacher. He has been credited, for example, through his imaginative classroom methods, with nurturing the Fredericton school of poets led by Bliss Carman and Charles G. D. Roberts. On 9 July 1878 he married Annie Connell Fisher (1858–1931), his former student at the Fredericton Collegiate, an accomplished classical scholar, and the daughter of William Fisher, a leading civil servant, loyalist, and Anglican. Theirs remained a love match, and Annie was a vital practical and emotional support in all Parkin's work. Together they had six daughters (four survived infancy) and one son.

After leaving Fredericton for the more opportune position of headmaster of Toronto's Upper Canada College (1895–1902), Parkin took a moribund institution and, explicitly following Thring's methods, succeeded in making it the premier private school in Canada. While he ably raised money, added buildings, engaged better masters, and reformed the curriculum, his core aim at the college remained the production of Christian gentlemen. He poured his energy into his own Sunday evening addresses to the boys and into his overall direction of the masters and work. He remained convinced that ‘nothing stamps a school as really great save the power of turning out men of high and noble character’ (Upper Canada College Times, Christmas 1902, 12).

Spokesman for a united empire

Parkin's main avenue for the realization of Christian idealism was not the school, however, but the British empire. Throughout his life, but especially during the years 1889–95, he was the leading advocate of imperial unity. His campaigns through thousands of speeches, hundreds of articles, and several books were wide-ranging. In the employ of the Imperial Federation League, he left Fredericton to stump across New Zealand and Australia throughout 1889. Based on the reputation he gained there, he was able to settle with his family in England and undertake five steady years of freelance lecturing and writing for the imperial cause all across Britain, sometimes sponsored by friends, the league, or other organizations, often working from personal contacts. His principal manifesto appeared as Imperial Federation: the Problem of National Unity (1892), and a school textbook, Round the Empire (1892), sold 200,000 copies and went through four editions up to 1919. He published a large wall map that effectively illustrated the unity of Britain's oceanic empire. He also lectured extensively across Canada, and began then his long affiliation with The Times, for which he wrote a series of extensive letters on Canadian history and geography (published as The Great Dominion, 1895). These were often difficult campaigns for Parkin—quite aside from the dire personal financial circumstances from which he operated. Many Canadian imperialists were wary of being too closely tied to a formally federated British empire where Britain by force of numbers would have the controlling hand. Yet many British imperialists felt that the colonies were not paying their fair share of imperial defence and other burdens. Parkin had to bridge these two positions. Controversy arose: there were celebrated disputes with the veteran Canadian politician and high commissioner Charles Tupper, which forced the dissolution of the Imperial Federation League in 1893, and a series of attacks on Goldwin Smith's anti-imperialism and North American continentalism.

Despite the spiritual motivation of Parkin's imperialism, he did not ignore the practical arguments favouring imperial unity. Influenced by J. R. Seeley and A. T. Mahan, Parkin pointed out to the British that, as an oceanic empire, their world influence rested on sea power. Given the realities of steamship distances, and the resultant dependencies on coal supplies and coaling bases, the empire desperately needed to retain, for commerce or defence, the quadrilateral of Australasia, South Africa, Canada, and the United Kingdom, and all the connecting islands and waterways. Trade, communications, military power, and cultural and religious influence depended on this geopolitical configuration. Without it, Britain would sink within fifty years, he presciently remarked, into the ranks of the second-class powers before the rising land-based empires of Russia and the United States; the fates of Spain and Portugal were suggestive. Similarly, Parkin pointed out to Canadians and Australians that, without the empire, the individual dominions would be battered about the world stage by aggressive superpowers; the recent experiences of Venezuela and Cuba were instructive. Self-interest, then, combined with the communications revolution of fast steamships, the telegraph, undersea cables, and connecting railways and canals across an ‘all-red’ route ably defended, combined with common language, literature, and culture, made a united empire possible.

Parkin naturally articulated Canada's position in a united empire. He sought to consolidate his native country's imperial place, especially in the face of a then hostile and continentalist United States. For Parkin imperial unity was never a subsuming of Canada's interests to British colonial administration, but rather a chance for Canada's fledgeling national ambitions to have reasonable scope on the world stage. Indeed, as the oldest and senior dominion, as the geopolitical linchpin in the all-red route, as a nation built on loyalty to the empire, with open spaces for immigrants, bountiful natural resources, and the wellspring of racial vigour engendered by northern climate, Canada was the ‘keystone’ of empire. He urged Canada, based on these Canadian traditions and characteristics, to accept its destiny and mature from weak colony to strong imperial partner. In Canada he effectively lobbied for practical measures to unite the empire: all-red-route telegraph cables, imperial penny postage, more effective colonial conferences, trade preferences, and, following especially vocal public pressure on his part in 1899–1902, sending Canadian contingents to fight in the South African War.

The pan-Britannic union was not an end in itself, however, or a means for jingoism, militarism, or financial profiteering. Rather, Parkin saw a stronger empire, much as he viewed education, as a vehicle for the realization of idealist principles. With imperial power came moral responsibility. In an entirely characteristic speech, he noted in 1894 that the Anglo-Saxon race ‘has temptations of an exceptional kind to yield itself to mere materialism, to forget that the things of the spirit are what endure and conquer in the end’. Anglo-Saxons must not ‘lose the great moral purposes of life in the race for gain’. They must view the empire as a means of spiritual regeneration:

The more clearly we realize the growing power, the ever widening influence, the increasing prestige of the empire, the more surely will the thought turn us to self-examination and self-improvement. ... Once realize what the expansion of our race in new lands means, and we cannot but turn with new earnestness to grapple with the moral and social problems which lie all around us. (Parkin MSS, ‘The Christian responsibilities of empire’, 22987–22990, 22970)

A strong, united empire would be a vehicle for pan-Britannic idealism, leading to the moral reform especially of the imperialists at home threatened by growing materialism and social declension, as well as to the uplift of subject peoples abroad. In a telling phrase, he saw himself as ‘a wandering Evangelist of Empire’. He was also labelled an ‘apostle’, ‘missionary’, or ‘lay preacher’ of empire.

Parkin's imperial campaigns eventually won his family moderate prosperity and social respectability. He became the confidant of prime ministers, leading educators, governors-general, and world-class thinkers. He personally influenced the imperial ideas of Asquith, Rosebery, Milner, Churchill, and Amery, and moved tens of thousands of others to cheering support. His name was coupled by contemporaries with those of Seeley, Kipling, and Rhodes as the leading advocates of the ‘new imperialism’, and his personal papers contain scores of newspaper clippings and private letters assigning to him the key role in swaying public opinion to the imperial cause.

The Rhodes Scholarship Trust

Because of his long educational and imperial experience, Parkin was invited in 1902 to be the first organizing secretary of the Rhodes Scholarship Trust. He travelled all over the empire and the United States several times before his retirement in 1920, and established the scholarships on a permanent and prestigious basis. His home at Goring-on-Thames became a meeting place for current and former Rhodes scholars as well as for a host of empire-wide visitors. From this position he continued his imperial speaking and writing, publishing biographies of John A. Macdonald, the first prime minister of Canada (1908), and—within a larger account of the scholarships—Cecil Rhodes (1912) which emphasized their subjects' imperial virtues. He campaigned vigorously during the First World War to keep idealism's lessons front and centre and to build on the imperial unity being concretely demonstrated by the dominions on the battlefields. In 1917–18 the British government asked Parkin to use his Rhodes scholarship contacts to lecture all over the United States to counter anti-British or neutralist sentiment there. After the war he readily accepted the new definitions of dominion autonomy which evolved from the peace conference, for his imperialism had always favoured the moral and spiritual unity of empire, displayed so clearly in the war, over any formal, constitutional arrangement. At the end of his life he devoted ever more time to reform of the Church of England, in which he was a prominent lay leader, to meet its National Church and imperial potential. Many honours came his way—honorary doctorates from several universities, including his beloved Oxford, a CMG in 1898, and a KCMG in 1920.

Parkin was a tall man, with a thin, somewhat tired-looking face. Sporting a moustache, narrow side whiskers, and shaggy brown hair, he had piercing, grey-blue eyes that suggested his enormous physical energy and moral earnestness. His remarkably deep and reasonant voice easily filled a hall of ten thousand people before the age of microphones, and the torrential rate of his delivery, often for two hours, held his audiences transfixed. Intense in public life, he exhibited a private sense of humour, with a great capacity for personal friendship and small kindnesses, and took much solace in quiet family times. Parkin died at his home, 7 Chelsea Court, London, of influenza on 25 June 1922, and was buried at Goring-on-Thames in the old churchyard overlooking the garden of his former house.

Terry Cook

Sources

T. Cook, ‘“Apostle of Empire”: Sir George Parkin and imperial federation’, PhD diss, Queen's University, 1977 · T. Cook, ‘George R. Parkin and the concept of Britannic idealism’, Journal of Canadian Studies, 10 (Aug 1975), 15–31 · T. Cook, ‘A reconstruction of the world: George R. Parkin's British empire map of 1893’, Cartographica, 21 (winter 1984), 53–65 · C. Berger, The sense of power: studies in the ideas of Canadian imperialism, 1867–1914 (1970) · A. B. McKillop, A disciplined intelligence: critical inquiry and Canadian thought in the Victorian era (1979) · R. B. Howard, Upper Canada College, 1829–1979: Colborne's legacy (1979) · J. Willison, Sir George Parkin (1929) · D. Cole, ‘Canada's “nationalistic” imperialists?’, Journal of Canadian Studies, 5 (Aug 1970), 44–9 · DNB · CGPLA Eng. & Wales (1922) · private information (2004)

Archives

CUL, letters and papers · NA Canada, corresp. and papers :: Bodl. Oxf., Lord Milner MSS · Bodl. RH, corresp. with Sir Francis Wylie · NA Canada, George T. Denison MSS · NA Canada, Raleigh Parkin MSS · NA Canada, W. L. and Maude Grant MSS · NA Canada, Lord Minto MSS · NA Canada, Sir Sandford Fleming MSS · Queen's University, Kingston, Ontario, Bliss Carman MSS

Likenesses

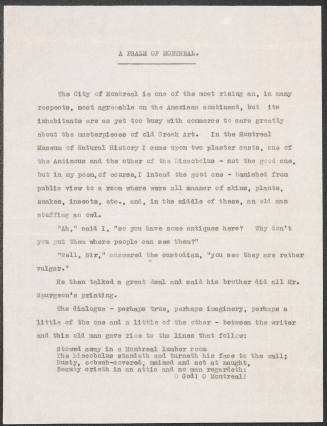

W. Stoneman, photograph, 1920, NPG [see illus.] · F. Varley, oils, 1921–2, National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa · E. Whitney Smith, bust, exh. RA 1928, Bodl. RH · photographs, NA Canada, Parkin family papers

Wealth at death

£6227 8s. 4d.: probate, 5 Aug 1922, CGPLA Eng. & Wales

© Oxford University Press 2004–13

All rights reserved: see legal notice Oxford University Press

Terry Cook, ‘Parkin, Sir George Robert (1846–1922)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn, May 2006 [http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/35389, accessed 6 Aug 2013]

Sir George Robert Parkin (1846–1922): doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/35389

Person TypeIndividual

Last Updated8/7/24

at sea off the Cape of Good Hope, 1848 - 1914, London

Giessen, Hesse-Durmstadt, 1854 - 1925, Sturry Court, Kent

Salem, Indiana, 1838 - 1905, Lake Sunapee, New Hampshire

Swanmore, England, 1869 - 1944, Toronto

London, 1845 - 1927, Clonmel, Ireland