Ernest Schelling

Belvidere, New Jersey, 1876 - 1939, New York

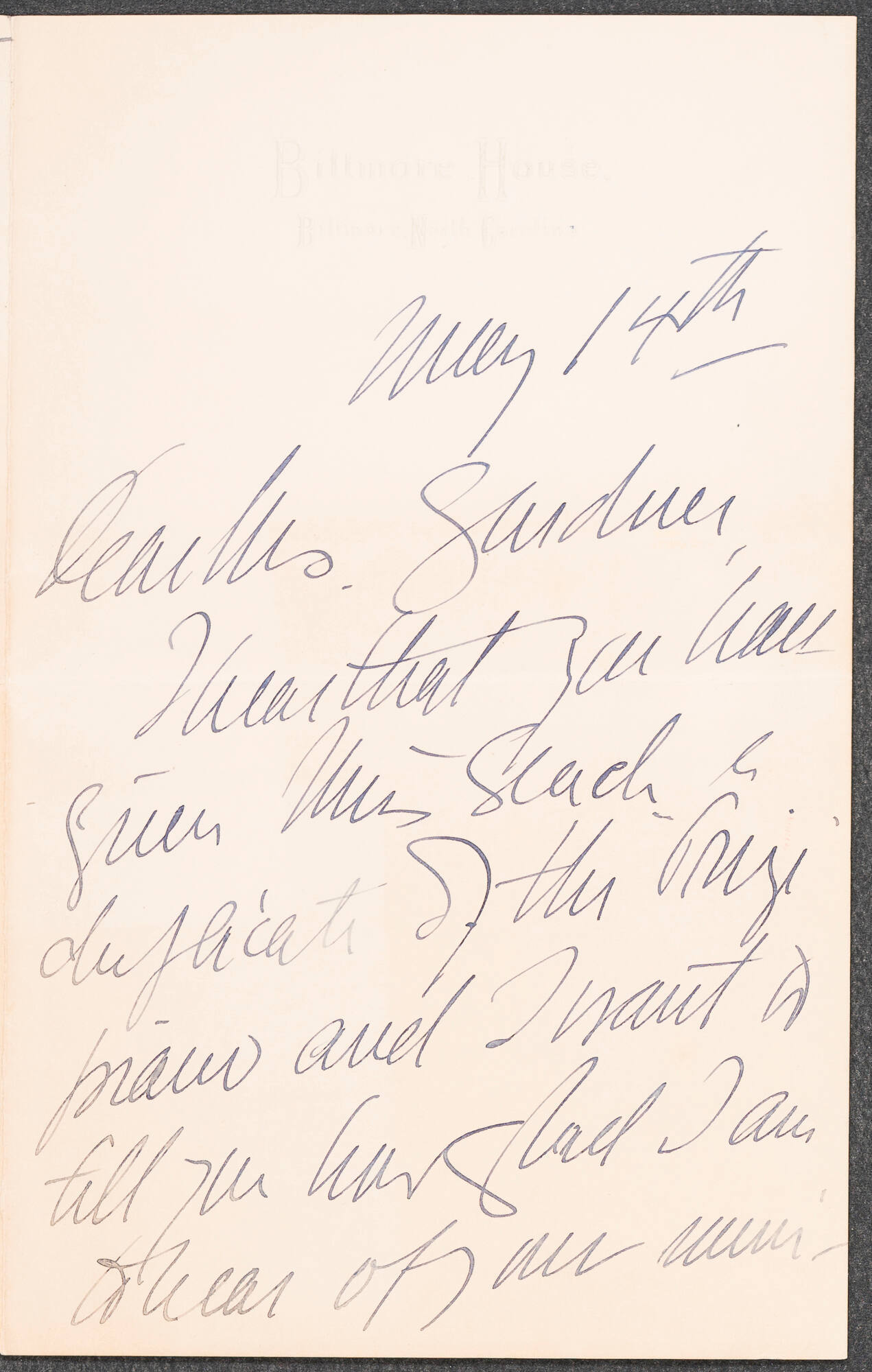

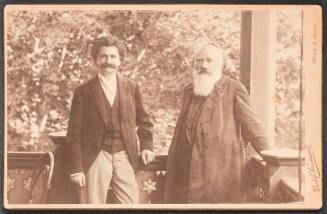

Schelling's studies continued in central Europe with leading pedagogues: Isidor Philipp, Dionys Pruckner (student of Franz Liszt), Percy Goetschius (theory), Theodor Leschetizky, Karl Heinrich Barth, Moritz Moszkowski, and Hans Huber (organ and composition). At age ten he played for Brahms. Studying music, languages, and literature so strenuously and concertizing throughout Europe from age twelve to eighteen damaged his health (neuritis in his arms and hands) and jeopardized his future. Later he credited his last master, Ignace Jan Paderewski, for practice methods and techniques that enabled him to make the transition from child prodigy to mature artist. They remained lifelong friends.

In 1900 Schelling became court musician to the Grand Duke Johann-Albrecht of Mecklenburg-Schwerin, whose wife Princess Elizabeth of Saxe-Weimar-Eisenach, the sister of the emperor, had studied with Liszt. In 1903-1904 he undertook an international tour and was among the first American-born artists to concertize in Latin America. Playing 186 concerts in eighteen months, Schelling made his North American debut as a mature artist on 24-25 February 1904 with the Boston Symphony under Wilhelm Gericke, fulfilling the artistic promise of the former child prodigy. It was through Paderewski, in Boston, that Schelling met Lucie How Draper, whom he married in 1905. They had no children.

Schelling's virtuosity as a pianist extended to composition, which began to develop at age three, with "Mon Premier Pas," op. 1. In 1907 his "Suite fantastique pour piano et orchestre," op. 7, premiered in Amsterdam with Willem Mengelberg conducting the Concertgebouw and the composer at the piano. (He would often lead from the piano, a feat popular with the public.) His success as a composer and performer continued to attract international attention with "Impressions from an Artist's Life, Symphonic Variations for Orchestra and Piano" (1915) and Concerto for Violin and Orchestra (1916). Both premiered with the Boston Symphony under Karl Muck. "Impressions" was the first American work to figure on a Toscanini program. Schelling's compositions were performed by orchestras with himself and other leading soloists, including Paderewski, who requested that Schelling write "a short Barcarolle" for his repertoire. This resulted in "Nocturne à Raguse" (1924), which Paderewski played seventy-eight times in one season and also recorded for the Victor label. "Theme and Variations" (1904) had already been dedicated to Paderewski.

An event of deep significance to Schelling was his military service during World War I. Completing officers' training at Fort Myer, Virginia, he enlisted in April 1917 on the day the United States declared war. He served first as a captain and then as a major with the American Expeditionary Force and was assigned to the Intelligence Branch of the general staff. Judged "a brilliant intelligence officer" and praised publicly for his "discipline, duty and devotion to his country," Schelling maintained an active status in the Military Intelligence Reserve throughout his life. He was also an early and active member of the International Entente against the Third International to combat communism. He received the Distinguished Service Medal (U.S.), Légion d'Honneur (France), and Polonia Restituta (Poland).

Schelling's war service inspired his most dramatic composition, "A Victory Ball, Fantasy for Orchestra" (1923), after the poem by Alfred Noyes and premiered by Leopold Stokowski with the Philadelphia Orchestra. He dedicated it "To the Memory of an American Soldier."

Schelling was active in numerous public enterprises. His social conscience and generosity were expressed in the performances he organized for needy colleagues. As first president (1929-1939) of the Edward MacDowell Artists' Colony in Peterborough, New Hampshire, he promoted its expansion and funding, and in 1932 he and his wife founded the Musicians' Emergency Fund, Inc. Schelling's international reputation as pianist, composer, and innovator led to his inclusion in a group of prominent citizens who met in 1936 with President Franklin D. Roosevelt to dramatize the need for a cabinet post of secretariat of fine arts. (The position never materialized.)

Schelling had already anticipated the need to cultivate an audience to assure the future of the symphony orchestra. "Music means culture," he said. "Culture means refinement. Refinement means good citizenship . . . Upon the intelligent listener . . . rests the responsibility." In 1924 he established his celebrated Children's and Young People's Concerts with the New York Philharmonic-Symphony Orchestra. Over the first four years children became acquainted with more than 100 orchestral works from composers ranging from Bach to Stravinsky. A series of five to fifteen performances per season at Carnegie Hall for an audience whose ages varied from five to the teenage years, the Children's and Young People's Concerts became a national fixture and under Schelling's direction they expanded to cities across the nation, from Boston to San Francisco. One hundred and eighty-seven concerts in New York City were carried nationally by the Columbia Broadcasting System beginning in 1930. Schelling gave demonstration concerts in the Netherlands in 1936. With the outbreak of World War II in 1939, the series in London was postponed. Schelling's first wife died in 1938, and the following year he married Helen Huntington Marshall, a young New Yorker dedicated to his work. They had no children.

Novelist and pianist John Erskine called Schelling "the musical god-father of America's younger generation." At the time of Schelling's death he was planning a book of his "Spoken Notes" to the audience, illustrated from his famous collection of 5,000 large-format, hand-colored glass lantern slides used at these concerts. He longed to concentrate again on composing and intended to write his memoirs. He died suddenly in New York City and was mourned by a host of friends and admirers. A thousand people attended his funeral.

Schelling was a composer with a keen, inventive mind. He had the power to sustain the gradual unfolding of ideas to build dramatic climaxes. By the logic of broadly arched voice, leading over suspended harmonies, often with ostinato figuration in counterpoint, Schelling created modern sonorities within the framework of late Romantic harmony. He used all the means at his disposal--both orchestrally and pianistically--and his works show great skill, colorful rhetoric, and brilliant virtuosity, originality, and expressiveness.

Bibliography

The Ernest Schelling Archives of some forty file drawers and 300 pounds of press clippings are located at the International Piano Archives of the University of Maryland at College Park. Otherwise the New York Philharmonic-Symphony Orchestra, Lincoln Center, holds materials relating to the Children's and Young People's Concerts. See also Thomas H. Hill, "Ernest Schelling (1876-1939): His Life and Contributions to Music Education through Educational Concerts" (Ph.D. diss., Catholic Univ. of America, 1970). Obituaries are in most major newspapers, 9 Dec. 1939.

Mary Louise Boehm

Back to the top

Citation:

Mary Louise Boehm. "Schelling, Ernest Henry";

http://www.anb.org/articles/18/18-01024.html;

American National Biography Online Feb. 2000.

Access Date: Tue Aug 06 2013 10:59:29 GMT-0400 (Eastern Standard Time)

Copyright © 2000 American Council of Learned Societies.

Person TypeIndividual

Last Updated8/7/24

New Malden, Kingston-upon-Thames, England, 1873 - 1951, Miami, Florida

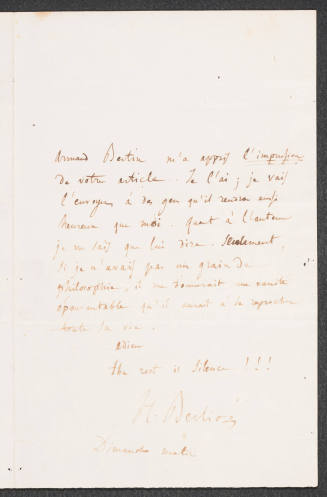

La Côte-Saint-André, France, 1803 - 1869, Paris

Hamburg, Germany, 1809 - 1847, Leipzig, Germany

Berlin, 1861 - 1935, Medfield, Massachusetts

Bayou Goula, Louisiana, 1844 - 1928, Watertown, Massachusetts

founded Stuttgart, 1810