Felix Mendelssohn-Bartholdy

Hamburg, Germany, 1809 - 1847, Leipzig, Germany

Contemporary accounts consistently describe the composer as having handsome, delicate features, expressive black eyes and curly black hair, with a Roman nose and pronounced sideburns, and standing approximately five feet, six inches in height. Despite his small frame, Mendelssohn was athletic and lean; he enjoyed hiking, swimming, riding and dancing. His manners were almost universally acknowledged as distinguished and elegant. British novelist William Makepeace Thackeray, on meeting the composer during the latter's trip to London in 1842, described Mendelssohn as having "the most beautiful face I ever saw, like what I imagine our Savior's to have been." Other descriptions make particular reference to his eyes, "dark, flashing," "unfathomable," shining from within. He was apparently a man of boundless energy and of an effusive nature, who was described by his longtime friend Eduard Devrient as "always bubbling over like champagne in a small glass."

His prodigious musical gifts allowed him to make significant contributions to the development of German musical life in general, most notably through his almost singlehanded revival of the works of Johann Sebastian Bach (1685-1750). Mendelssohn's efforts proved crucial in reestablishing the older composer at the forefront of Western music, consequently affecting the very concept of art music ever since.

Through incorporating into his own compositions diverse elements from his musical heritage (i.e., from both Classical and Romantic sources, to which were added influences of composers of the Italian Renaissance as well as of J.S. Bach), combined with his own highly original contributions, Mendelssohn forged a musical language that was distinctly his own. As a result, he became known as the foremost living composer in Germany by the 1830s, a reputation that he enjoyed until his death in 1847.

Curiously, however, after Mendelssohn's death his music fell into an obscurity from which, in many regards, it has still not completely emerged. Of the world's most significant composers, his music is probably the least known to the public or made the subject of scholarly research. Even at the time of this writing, several titles of his substantial body of works has not yet been published.

A combination of several factors contributed to this neglect of Mendelssohn's works. First of all, Mendelssohn's career was positioned between that of Ludwig van Beethoven and Richard Wagner, the two Titans of nineteenth century German music, the large scope of whose work unfortunately diminished that of Mendelssohn and his no-less-significant contemporaries (i.e., Carl Maria von Weber, Robert and Clara Schumann, etc.) in comparison. While Mendelssohn's musical language does not reflect harmonic or structural innovations on the scale of that of Beethoven or Wagner, he nevertheless created a large body of finely-crafted works that bear the indelible stamp of his personal style.

The generally small scale of the musical genres in which Mendelssohn worked (i.e., song, or Lieder), as well as of larger scale sacred works such as oratorio, etc. were also becoming increasingly anachronistic; the changing musical tastes both of the public and of composers increasingly favored large scale works such as symphonies and operas for the remainder of the nineteenth century and beyond. Compared to the monumental, highly dramatic works that gained increasing popularity throughout the nineteenth century, the works of graceful beauty and modest proportions at which Mendelssohn excelled were increasingly dismissed as quaint and insignificant.

Finally, the rising tide of anti-Semitism that swept through mid-nineteenth century Europe -- the flames of which were fanned through the writings of, among others, the ambitious and vehemently anti-Semitic German composer Richard Wagner -- and culminating in the pogroms instituted during the Nazi era (a time during which performances of Mendelssohn's music were banned, and his name erased from history books), also had a tremendously negative impact on the reputation of Mendelssohn, a Protestant of Jewish heritage.

By the 1880s, Mendelssohn's reputation had diminished substantially, prompting British playwright George Bernard Shaw to compare the composer's legacy to the "kid glove gentility" and "conventional sentimentality" of a vanished world.

Fortunately, however, increased attention is currently being focused on Mendelssohn's work, and efforts are underway by scholars internationally to publish the composer's complete works. Over the past two decades a resurgence of scholarship and focus on what musicologist Carl Dahlhaus has termed "the Mendelssohn problem" has resulted in a more objective reevaluation and renewed appreciation of the composer's works and legacy.

Felix Mendelssohn died in Leipzig on November 4, 1847, at the age of thirty-eight. His influence on Western music of the era, represented by the large number of works that produced and his tireless efforts in performing, conducting and resurrecting music of the past, has left an indelible imprint on our shared musical culture that may be perceived even today.

https://loc.gov/item/ihas.200156439 I.S. 10/23/2018

Jakob Ludwig Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy[n 1] (3 February 1809 – 4 November 1847), born and widely known as Felix Mendelssohn,[n 2] was a German composer, pianist, organist and conductor of the early romantic period. Mendelssohn wrote symphonies, concertos, oratorios, piano music and chamber music. His best-known works include his Overture and incidental music for A Midsummer Night's Dream, the Italian Symphony, the Scottish Symphony, the overture The Hebrides, his mature Violin Concerto, and his String Octet. His Songs Without Words are his most famous solo piano compositions. After a long period of relative denigration due to changing musical tastes and antisemitism in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, his creative originality has been re-evaluated. He is now among the most popular composers of the romantic era.

A grandson of the philosopher Moses Mendelssohn, Felix Mendelssohn was born into a prominent Jewish family. He was brought up without religion until the age of seven, when he was baptised as a Reformed Christian. Felix was recognised early as a musical prodigy, but his parents were cautious and did not seek to capitalise on his talent.

Mendelssohn enjoyed early success in Germany, and revived interest in the music of Johann Sebastian Bach, notably with his performance of the St Matthew Passion in 1829. He became well received in his travels throughout Europe as a composer, conductor and soloist; his ten visits to Britain – during which many of his major works were premiered – form an important part of his adult career. His essentially conservative musical tastes set him apart from more adventurous musical contemporaries such as Franz Liszt, Richard Wagner, Charles-Valentin Alkan and Hector Berlioz. The Leipzig Conservatoire, which he founded, became a bastion of this anti-radical outlook.

Life

Childhood

Mendelssohn aged 12 (1821) by Carl Joseph Begas

Felix Mendelssohn was born on 3 February 1809, in Hamburg, at the time an independent city-state,[n 3] in the same house where, a year later, the dedicatee and first performer of his Violin Concerto, Ferdinand David, would be born.[1] Mendelssohn's father, the banker Abraham Mendelssohn, was the son of the German Jewish philosopher Moses Mendelssohn. His mother, Lea Salomon, was a member of the Itzig family and a sister of Jakob Salomon Bartholdy.[2] Mendelssohn was the second of four children; his older sister Fanny also displayed exceptional and precocious musical talent.[3]

The family moved to Berlin in 1811, leaving Hamburg in disguise in fear of French reprisal for the Mendelssohn bank's role in breaking Napoleon's Continental System blockade.[4] Abraham and Lea Mendelssohn sought to give their children – Fanny, Felix, Paul and Rebecka – the best education possible. Fanny became a pianist well known in Berlin musical circles as a composer; originally Abraham had thought that she, rather than Felix, would be the more musical. But it was not considered proper, by either Abraham or Felix, for a woman to pursue a career in music, so she remained an active but non-professional musician.[5] Abraham was initially disinclined to allow Felix to follow a musical career until it became clear that he was seriously dedicated.[6]

Mendelssohn grew up in an intellectual environment. Frequent visitors to the salon organised by his parents at the family's home in Berlin included artists, musicians and scientists, among them Wilhelm and Alexander von Humboldt, and the mathematician Peter Gustav Lejeune Dirichlet (whom Mendelssohn's sister Rebecka would later marry).[7] The musician Sarah Rothenburg has written of the household that "Europe came to their living room".[8]

Surname

Abraham Mendelssohn renounced the Jewish religion; he and his wife decided not to have Felix circumcised, in contravention of the Jewish tradition.[9] Felix and his siblings were first brought up without religious education, and were baptised by a Reformed Church minister in 1816,[10] at which time Felix was given the additional names Jakob Ludwig. Abraham and his wife Lea were baptised in 1822, and formally adopted the surname Mendelssohn Bartholdy (which they had used since 1812) for themselves and their children.[11] The name Bartholdy was added at the suggestion of Lea's brother, Jakob Salomon Bartholdy, who had inherited a property of this name in Luisenstadt and adopted it as his own surname.[12] In an 1829 letter to Felix, Abraham explained that adopting the Bartholdy name was meant to demonstrate a decisive break with the traditions of his father Moses: "There can no more be a Christian Mendelssohn than there can be a Jewish Confucius". (Letter to Felix of 8 July 1829).[13] On embarking on his musical career, Felix did not entirely drop the name Mendelssohn as Abraham had requested, but in deference to his father signed his letters and had his visiting cards printed using the form 'Mendelssohn Bartholdy'.[14] In 1829, his sister Fanny wrote to him of "Bartholdy [...] this name that we all dislike".[15]

Career

Musical education

Mendelssohn began taking piano lessons from his mother when he was six, and at seven was tutored by Marie Bigot in Paris.[16] Later in Berlin, all four Mendelssohn children studied piano with Ludwig Berger, who was himself a former student of Muzio Clementi.[17] From at least May 1819 Mendelssohn (initially with his sister Fanny) studied counterpoint and composition with Carl Friedrich Zelter in Berlin.[18] This was an important influence on his future career. Zelter had almost certainly been recommended as a teacher by his aunt Sarah Levy, who had been a pupil of W. F. Bach and a patron of C. P. E. Bach. Sarah Levy displayed some talent as a keyboard player, and often playing with Zelter's orchestra at the Berliner Singakademie; she and the Mendelssohn family were among its leading patrons. Sarah had formed an important collection of Bach family manuscripts which she bequeathed to the Singakademie; Zelter, whose tastes in music were conservative, was also an admirer of the Bach tradition.[19] This undoubtedly played a significant part in forming Felix Mendelssohn's musical tastes. His works show his study of Baroque and early classical music. His fugues and chorales especially reflect a tonal clarity and use of counterpoint reminiscent of Johann Sebastian Bach, by whose music he was deeply influenced.[20]

Early maturity

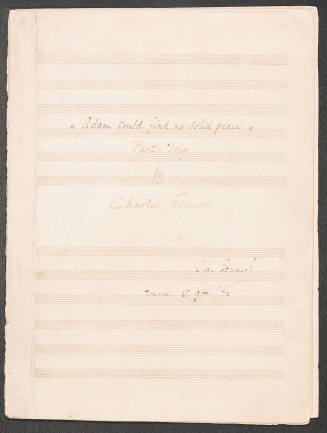

First page of the manuscript of Mendelssohn's Octet (1825) (now in the US Library of Congress)

Mendelssohn probably made his first public concert appearance at the age of nine, when he participated in a chamber music concert accompanying a horn duo.[21] He was a prolific composer from an early age. As an adolescent, his works were often performed at home with a private orchestra for the associates of his wealthy parents amongst the intellectual elite of Berlin.[22] Between the ages of 12 and 14, Mendelssohn wrote 12 string symphonies for such concerts, and a number of chamber works.[23] His first work, a piano quartet, was published when he was 13. It was probably Abraham Mendelssohn who procured the publication of this quartet by the house of Schlesinger.[24] In 1824 the 15-year-old wrote his first symphony for full orchestra (in C minor, Op. 11).[25]

At age 16 Mendelssohn wrote his String Octet in E-flat major, a work which has been regarded as "mark[ing] the beginning of his maturity as a composer."[26] This Octet and his Overture to Shakespeare's A Midsummer Night's Dream, which he wrote a year later in 1826, are the best-known of his early works. (Later, in 1843, he also wrote incidental music for the play, including the famous "Wedding March".) The Overture is perhaps the earliest example of a concert overture—that is, a piece not written deliberately to accompany a staged performance but to evoke a literary theme in performance on a concert platform; this was a genre which became a popular form in musical romanticism.[27]

In 1824 Mendelssohn studied under the composer and piano virtuoso Ignaz Moscheles, who confessed in his diaries[28] that he had little to teach him. Moscheles and Mendelssohn became close colleagues and lifelong friends. The year 1827 saw the premiere – and sole performance in his lifetime – of Mendelssohn's opera Die Hochzeit des Camacho. The failure of this production left him disinclined to venture into the genre again.[29]

Besides music, Mendelssohn's education included art, literature, languages, and philosophy. He had a particular interest in classical literature[30] and translated Terence's Andria for his tutor Heyse in 1825; Heyse was impressed and had it published in 1826 as a work of "his pupil, F****" [i.e. "Felix" (asterisks as provided in original text)].[31][n 4] This translation also qualified Mendelssohn to study at the Humboldt University of Berlin, where from 1826 to 1829 he attended lectures on aesthetics by Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel, on history by Eduard Gans and on geography by Carl Ritter.[33]

Meeting Goethe and conducting Bach

In 1821 Zelter introduced Mendelssohn to his friend and correspondent Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (then in his seventies), who was greatly impressed by the child, leading to perhaps the earliest confirmed comparison with Mozart in the following conversation between Goethe and Zelter:

"Musical prodigies ... are probably no longer so rare; but what this little man can do in extemporizing and playing at sight borders the miraculous, and I could not have believed it possible at so early an age." "And yet you heard Mozart in his seventh year at Frankfurt?" said Zelter. "Yes", answered Goethe, "... but what your pupil already accomplishes, bears the same relation to the Mozart of that time that the cultivated talk of a grown-up person bears to the prattle of a child."[34]

Mendelssohn was invited to meet Goethe on several later occasions,[35] and set a number of Goethe's poems to music. His other compositions inspired by Goethe include the overture Calm Sea and Prosperous Voyage (Op. 27, 1828), and the cantata Die erste Walpurgisnacht (The First Walpurgis Night, Op. 60, 1832).[36]

In 1829, with the backing of Zelter and the assistance of the actor Eduard Devrient, Mendelssohn arranged and conducted a performance in Berlin of Bach's St Matthew Passion. Four years previously his grandmother, Bella Salomon, had given him a copy of the manuscript of this (by then all-but-forgotten) masterpiece.[37] The orchestra and choir for the performance were provided by the Berlin Singakademie. The success of this performance, one of the very few since Bach's death and the first ever outside of Leipzig,[n 5] was the central event in the revival of Bach's music in Germany and, eventually, throughout Europe.[39] It earned Mendelssohn widespread acclaim at the age of 20. It also led to one of the few explicit references which Mendelssohn made to his origins: "To think that it took an actor and a Jew's son to revive the greatest Christian music for the world!"[40][41]

Over the next few years Mendelssohn travelled widely. His first visit to England was in 1829; other places visited during the 1830s included Vienna, Florence, Milan, Rome and Naples, in all of which he met with local and visiting musicians and artists. These years proved to be the germination for some of his most famous works, including the Hebrides Overture and the Scottish and Italian symphonies.[42]

Düsseldorf

On Zelter's death in 1832, Mendelssohn had hopes of succeeding him as conductor of the Singakademie; but at a vote in January 1833 he was defeated for the post by Carl Friedrich Rungenhagen. This may have been because of Mendelssohn's youth, and fear of possible innovations; it was also suspected by some to be attributable to his Jewish ancestry.[43] Following this rebuff, Mendelssohn divided most of his professional time over the next few years between Britain and Düsseldorf, where he was appointed musical director (his first paid post as a musician) in 1833.[44]

In the spring of that year Mendelssohn directed the Lower Rhenish Music Festival in Düsseldorf, beginning with a performance of George Frideric Handel's oratorio Israel in Egypt prepared from the original score, which he had found in London. This precipitated a Handel revival in Germany, similar to the reawakened interest in J. S. Bach following his performance of the St Matthew Passion.[45] Mendelssohn worked with the dramatist Karl Immermann to improve local theatre standards, and made his first appearance as an opera conductor in Immermann's production of Mozart's Don Giovanni at the end of 1833, where he took umbrage at the audience's protests about the cost of tickets. His frustration at his everyday duties in Düsseldorf, and the city's provincialism, led him to resign his position at the end of 1834. He had offers from both Munich and Leipzig for important musical posts, namely, direction of the Munich Opera, the editorship of the prestigious Leipzig music journal the Allgemeine musikalische Zeitung, and direction of the Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra; he accepted the latter in 1835.[46][47]

Leipzig and Berlin

Mendelssohn's study in Leipzig

In Leipzig Mendelssohn concentrated on developing the town's musical life, working with the orchestra, the opera house, the Thomanerchor (of which Bach had been a director), and the city's other choral and musical institutions. Mendelssohn's concerts included, in addition to many of his own works, three series of "historical concerts" featuring music of the eighteenth century, and a number of works by his contemporaries.[48] He was deluged by offers of music from rising and would-be composers; among these was Richard Wagner, who submitted his early Symphony, the score of which, to Wagner's disgust, Mendelssohn lost or mislaid.[49] Mendelssohn also revived interest in the music of Franz Schubert. Robert Schumann discovered the manuscript of Schubert's Ninth Symphony and sent it to Mendelssohn, who promptly premiered it in Leipzig on 21 March 1839, more than a decade after Schubert's death.[50]

A landmark event during Mendelssohn's Leipzig years was the premiere of his oratorio Paulus, (the English version of this is known as St. Paul), given at the Lower Rhenish Festival in Düsseldorf in 1836, shortly after the death of the composer's father, which much affected him; Felix wrote that he would "never cease to endeavour to gain his approval [...] although I can no longer enjoy it".[51] St. Paul seemed to many of Mendelssohn's contemporaries to be his finest work, and sealed his European reputation.[52]

When Friedrich Wilhelm IV came to the Prussian throne in 1840 with ambitions to develop Berlin as a cultural centre (including the establishment of a music school, and reform of music for the church), the obvious choice to head these reforms was Mendelssohn. He was reluctant to undertake the task, especially in the light of his existing strong position in Leipzig.[53] Mendelssohn nonetheless spent some time in Berlin, writing some church music, and, at the King's request, music for productions of Sophocles's Antigone (1841 - an overture and seven pieces) and Oedipus at Colonus (1845), A Midsummer Night's Dream (1843) and Racine's Athalie (1845).[n 6] But the funds for the school never materialised, and various of the court's promises to Mendelssohn regarding finances, title, and concert programming were broken. He was therefore not displeased to have the excuse to return to Leipzig.[55]

In 1843 Mendelssohn founded a major music school – the Leipzig Conservatory, now the Hochschule für Musik und Theater "Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy".[n 7] where he persuaded Ignaz Moscheles and Robert Schumann to join him. Other prominent musicians, including the string players Ferdinand David and Joseph Joachim and the music theorist Moritz Hauptmann, also became staff members.[56] After Mendelssohn's death in 1847, his musically conservative tradition was carried on when Moscheles succeeded him as head of the Conservatory.[57]

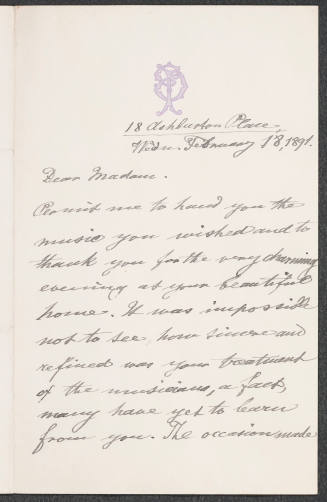

Mendelssohn in Britain

Mendelssohn first visited Britain in 1829, where Moscheles, who had already settled in London, introduced him to influential musical circles. In the summer he visited Edinburgh, where he met among others the composer John Thomson, whom he later recommended for the post of Professor of Music at Edinburgh University.[58] He made ten visits to Britain, lasting about 20 months; he won a strong following, which enabled him to make a good impression on British musical life. [59] He composed and performed, and also edited for British publishers the first critical editions of oratorios of Handel and of the organ music of J. S. Bach. Scotland inspired two of his most famous works: the overture The Hebrides (also known as Fingal's Cave); and the Scottish Symphony (Symphony No. 3).[60] An English Heritage blue plaque commemorating Mendelssohn's residence in London was placed at 4 Hobart Place in Belgravia, London, in 2013.[61]

Mendelssohn's gravestone at the Dreifaltigkeitsfriedhof

His protégé, the British composer and pianist William Sterndale Bennett, worked closely with Mendelssohn during this period, both in London and Leipzig. He first heard Bennett perform in London in 1833 aged 17.[62][n 8] Bennett appeared with Mendelssohn in concerts in Leipzig throughout the 1836/1837 season.[64]

On Mendelssohn's eighth British visit in the summer of 1844, he conducted five of the Philharmonic concerts in London, and wrote: "[N]ever before was anything like this season – we never went to bed before half-past one, every hour of every day was filled with engagements three weeks beforehand, and I got through more music in two months than in all the rest of the year." (Letter to Rebecka Mendelssohn Bartholdy, Soden, 22 July 1844).[65] On subsequent visits Mendelssohn met Queen Victoria and her husband Prince Albert, himself a composer, who both greatly admired his music.[66][67]

Mendelssohn's oratorio Elijah was commissioned by the Birmingham Triennial Music Festival and premiered on 26 August 1846, at the Town Hall, Birmingham. It was composed to a German text translated into English by William Bartholomew, who authored and translated many of Mendelssohn's works during his time in England.[68][69]

On his last visit to Britain in 1847, Mendelssohn was the soloist in Beethoven's Piano Concerto No. 4 and conducted his own Scottish Symphony with the Philharmonic Orchestra before the Queen and Prince Albert.[70]

Death

Mendelssohn suffered from poor health in the final years of his life, probably aggravated by nervous problems and overwork. A final tour of England left him exhausted and ill, and the death of his sister, Fanny, on 14 May 1847, caused him further distress. Less than six months later, on 4 November, aged 38, Mendelssohn died in Leipzig after a series of strokes.[71] His grandfather Moses, Fanny, and both his parents had all died from similar apoplexies.[72][n 9] Felix's funeral was held at the Paulinerkirche, Leipzig, and he was buried at the Dreifaltigkeitsfriedhof I in Berlin-Kreuzberg. The pallbearers included Moscheles, Schumann and Niels Gade.[74] Mendelssohn had once described death, in a letter to a stranger, as a place "where it is to be hoped there is still music, but no more sorrow or partings."[75]

Personal life

Personality

View of Lucerne – watercolour by Mendelssohn, 1847

While Mendelssohn was often presented as equable, happy and placid in temperament, particularly in the detailed family memoirs published by his nephew Sebastian Hensel after the composer’s death;[76] this was misleading. The music historian R. Larry Todd notes "the remarkable process of idealization" of Mendelssohn's character "that crystallized in the memoirs of the composer's circle", including Hensel's.[77] The nickname "discontented Polish count" was given to Mendelssohn on account of his aloofness, and he referred to the epithet in his letters.[78] He was frequently given to fits of temper which occasionally led to collapse. Devrient mentions that on one occasion in the 1830s, when his wishes had been crossed, "his excitement was increased so fearfully ... that when the family was assembled ... he began to talk incoherently in English. The stern voice of his father at last checked the wild torrent of words; they took him to bed, and a profound sleep of twelve hours restored him to his normal state".[79] Such fits may be related to his early death.[72]

Mendelssohn was an enthusiastic visual artist who worked in pencil and watercolour, a skill which he enjoyed throughout his life.[80][81] His correspondences indicate that he could write with considerable wit in German and English – these letters are sometimes accompanied by humorous sketches and cartoons.[82]

Religion

On 21 March 1816, at the age of seven years, Mendelssohn was baptised with his brother and sisters in a home ceremony by Johann Jakob Stegemann, minister of the Evangelical congregation of Berlin's Jerusalem Church and New Church.[11] Although Mendelssohn was a conforming Christian as a member of the Reformed Church,[n 10] he was both conscious and proud of his Jewish ancestry and notably of his connection with his grandfather, Moses Mendelssohn. He was the prime mover in proposing to the publisher Heinrich Brockhaus a complete edition of Moses's works, which continued with the support of his uncle, Joseph Mendelssohn.[84] Felix was notably reluctant, either in his letters or conversation, to comment on his innermost beliefs; his friend Devrient wrote that "[his] deep convictions were never uttered in intercourse with the world; only in rare and intimate moments did they ever appear, and then only in the slightest and most humorous allusions".[85] Thus for example in a letter to his sister Rebecka, Mendelssohn rebukes her complaint about an unpleasant relative: "What do you mean by saying you are not hostile to Jews? I hope this was a joke [...] It is really sweet of you that you do not despise your family, isn't it?"[86] Some modern scholars have devoted considerable energy to demonstrate either that Mendelssohn was deeply sympathetic to his ancestors' Jewish beliefs, or that he was hostile to this and sincere in his Christian beliefs.[n 11]

Mendelssohn and his contemporaries

Giacomo Meyerbeer by Josef Kriehuber, 1847

Throughout his life Mendelssohn was wary of the more radical musical developments undertaken by some of his contemporaries. He was generally on friendly, if sometimes somewhat cool, terms with Hector Berlioz, Franz Liszt, and Giacomo Meyerbeer, but in his letters expresses his frank disapproval of their works, for example writing of Liszt that his compositions were "inferior to his playing, and [...] only calculated for virtuosos";[88] of Berlioz's overture Les francs-juges "[T]he orchestration is such a frightful muddle [...] that one ought to wash one's hands after handling one of his scores";[89] and of Meyerbeer's opera Robert le diable "I consider it ignoble", calling its villain Bertram "a poor devil".[90] When his friend the composer Ferdinand Hiller suggested in conversation to Mendelssohn that he looked rather like Meyerbeer – they were actually distant cousins, both descendants of Rabbi Moses Isserlis – Mendelssohn was so upset that he immediately went to get a haircut to differentiate himself.[91]

In particular, Mendelssohn seems to have regarded Paris and its music with the greatest of suspicion and an almost puritanical distaste. Attempts made during his visit there to interest him in Saint-Simonianism ended in embarrassing scenes.[92] It is significant that the only musician with whom Mendelssohn remained a close personal friend, Ignaz Moscheles, was of an older generation and equally conservative in outlook. Moscheles preserved this conservative attitude at the Leipzig Conservatory until his own death in 1870.[57]

Marriage and children

Mendelssohn's wife Cécile (1846) by Eduard Magnus

Mendelssohn married Cécile Charlotte Sophie Jeanrenaud (10 October 1817 – 25 September 1853), the daughter of a French Reformed Church clergyman, on 28 March 1837.[93] The couple had five children: Carl, Marie, Paul, Lili and Felix. The second youngest child, Felix August, contracted measles in 1844 and was left with impaired health; he died in 1851.[94] The eldest, Carl Mendelssohn Bartholdy (7 February 1838 – 23 February 1897), became a historian, and Professor of History at Heidelberg and Freiburg universities; he died in a psychiatric institution in Freiburg aged 59.[95] Paul Mendelssohn Bartholdy (1841–1880) was a noted chemist and pioneered the manufacture of aniline dye. Marie married Victor Benecke and lived in London. Lili married Adolph Wach, later Professor of Law at Leipzig University.[96]

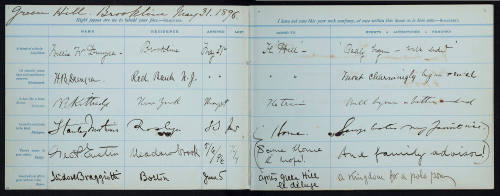

The family papers inherited by Marie and Lili's children form the basis of the extensive collection of Mendelssohn manuscripts, including the so-called "Green Books" of his correspondence, now in the Bodleian Library at Oxford University.[97] Cécile Mendelssohn Bartholdy died less than six years after her husband, on 25 September 1853.[98]

Jenny Lind

Jenny Lind

Mendelssohn became close to the Swedish soprano Jenny Lind, whom he met in October 1844. Papers confirming their relationship had not been made public.[99][n 12] In 2013 George Biddlecombe confirmed in the Journal of the Royal Musical Association that "The Committee of the Mendelssohn Scholarship Foundation possesses material indicating that Mendelssohn wrote passionate love letters to Jenny Lind entreating her to join him in an adulterous relationship and threatening suicide as a means of exerting pressure upon her, and that these letters were destroyed on being discovered after her death."[102]

Mendelssohn met and worked with Lind many times, and started an opera, Lorelei, for her, based on the legend of the Lorelei Rhine maidens; the opera was unfinished at his death. H

Person TypeIndividual

Last Updated1/11/25

Geisenheim, Germany, 1826 - 1890, Beverly, Massachusetts

La Côte-Saint-André, France, 1803 - 1869, Paris

Boston, 1848 - 1913, Vevey, Switzerland

founded Wiesbaden, Germany 1719 -