Sarah Orne Jewett

South Berwick, Maine, 1849 - 1909, South Berwick, Maine

The landscape surrounding her proved an influential tutor. Jewett was frequently sent outdoors as therapeutic treatment for her lifelong battle against rheumatoid arthritis, a condition that developed in early childhood. On her cross-country walks, she cultivated a love for flowers and herbs as she escaped the confines of the traditional classroom. Supplementing her education was an extensive family library, including not only traditional poets and novelists but also texts on history, philosophy, horticulture, medicine, theology, and the sciences. Jewett was never overtly religious, but her friendship with Harvard law professor Theophilus Parsons during the 1870s prompted interest in the teachings of Emanuel Swedenborg, an eighteenth-century Swedish scientist and theologian. Swedenborg held that nothing exists in isolation--the Divine is present in innumerable, joined forms--a concept underlying Jewett's belief in individual responsibility.

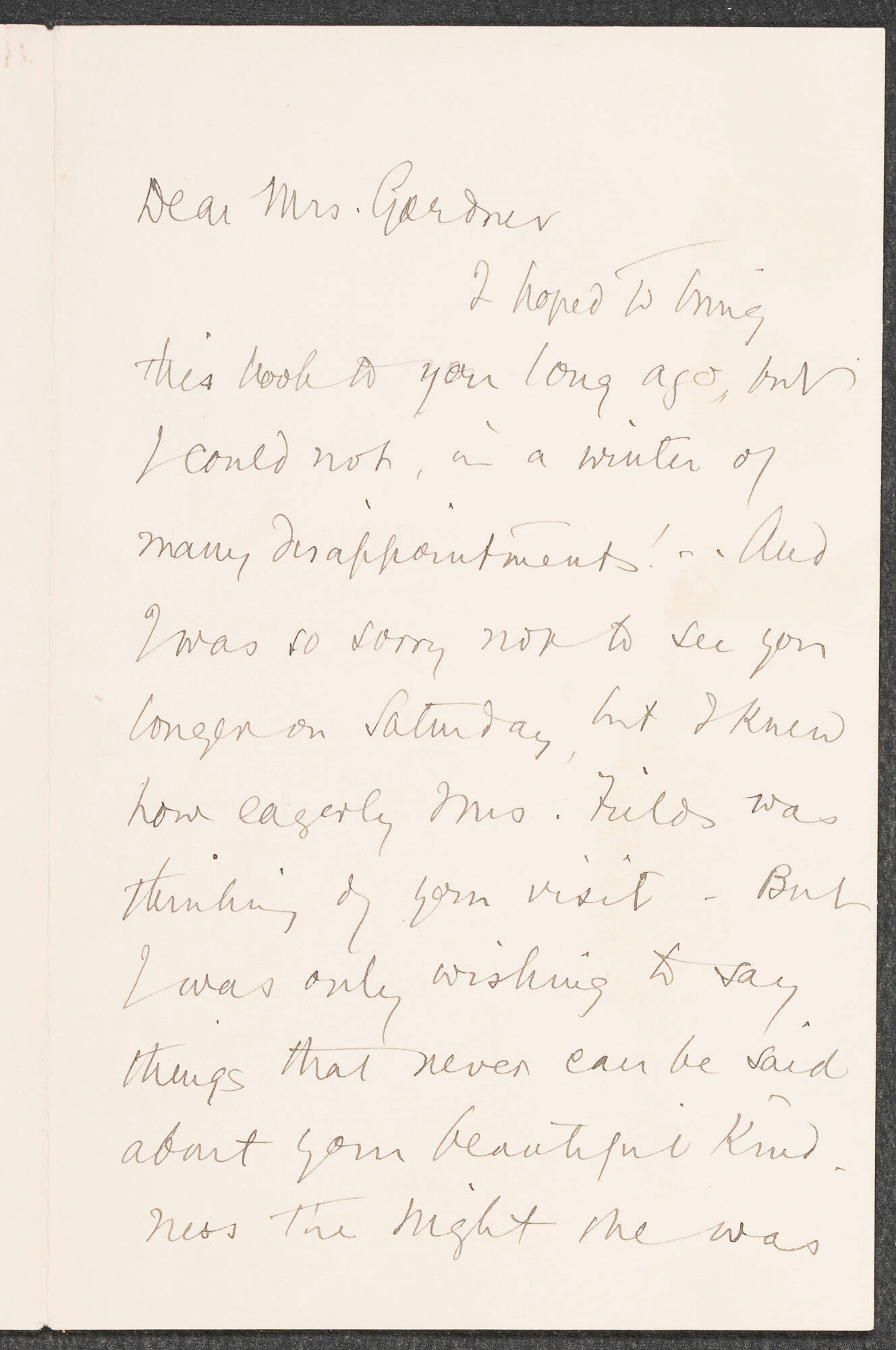

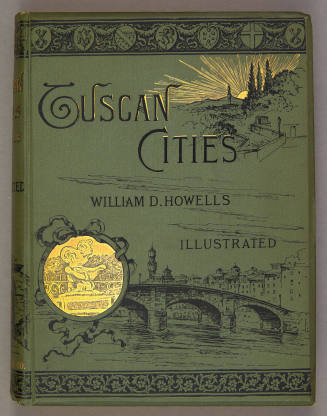

Published locally at age fourteen, the mature Jewett often neglected to mention her first regional publication, "Jenny Garrow's Lovers" (1868), a weak, conventional romance. She preferred to mark her literary debut with the 1869 Atlantic Monthly publication of "Mr. Bruce." Rejections of two stories followed as Jewett attempted to write conventional romances. In her 1871 correspondence with Atlantic editors James T. Fields and William Dean Howells, Jewett requested permission to develop "The Shore House" as a sketch rather than strengthening the plot as Howells had initially suggested. With Howells's editorial support, "The Shore House" (1873) became the first in an Atlantic Monthly series of Maine sketches that were collected in Deephaven (1877). These early works embody the descriptive style that Jewett continued to perfect throughout her literary career. She was influenced by the regional description and moral sensibility of Harriet Beecher Stowe's Pearl of Orr's Island (1862). Jewett later reflected that Deephaven was written as both a moral and a social education for her urban readers, validating the "grand, simple lives" of country people. In a letter to Jewett in 1875, Howells wrote, "You've got an uncommon feeling for talk--I hear your people."

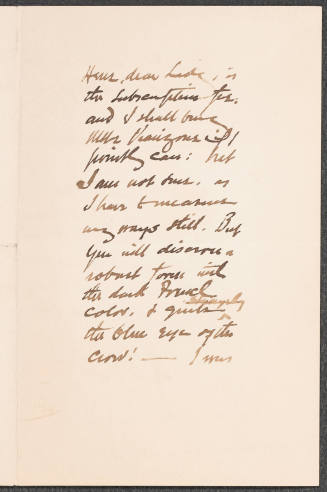

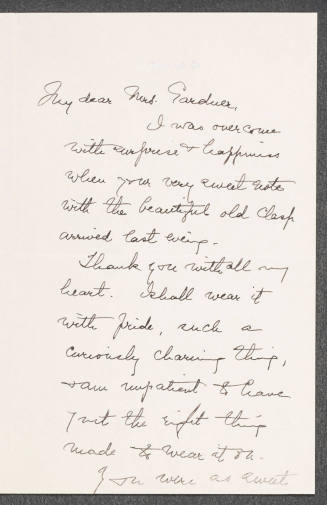

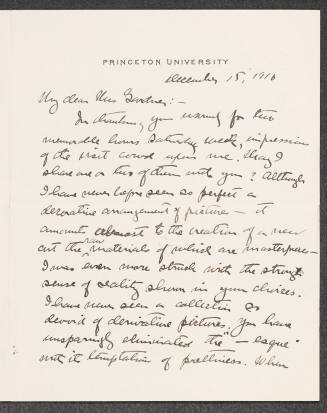

While she loved her Berwick home, Jewett was readily welcomed in the social circles of Boston, as were her literary sketches. She began a round of visits to Boston, New York, Philadelphia, Concord, and Washington, D.C., during the 1870s, fostering important literary friendships. Jewett's friends included the families of Howells, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, James Russell Lowell, Charles Eliot Norton, John Greenleaf Whittier, Julia Ward Howe, and Horace Elisha Scudder, editor of the Riverside Magazine. Following the shock of her father's death in 1878, Jewett found solace in further visits to these Bostonian friends. Distinctive among them was Annie Adams Fields, wife of publisher James T. Fields and hostess of one of Boston's most prominent literary salons. When James Fields died suddenly in 1881, the Jewett-Fields relationship flowered as the two women found friendship, humor, and literary encouragement in one another. Amiable traveling and living companions, the two women spent most of their following years in each other's company, visiting Europe and continuing to host American and European literati. Jewett never married.

In the following decade Jewett produced more than sixty articles and sketches, many of which were collected in A White Heron and Other Stories (1886). Her work also included three novels, A Country Doctor (1884), A Marsh Island (1885), and Betty Leicester (1890), as well as a history for young people, The Story of the Normans (1887). Like her short stories, Jewett's novels depict steadfast women in country settings and include moral reflection. A Country Doctor differs significantly in its feminist affirmation of the young heroine's self-reliance.

Jewett's revered work The Country of the Pointed Firs (1896) was first serialized in the Atlantic. Its publication was greeted warmly both at home and abroad; Rudyard Kipling wrote Jewett in 1897, saying, "It's immense--it is the very life." A twenty-sketch narrative of one woman's visit to Dunnet Landing, the work observes the joy and worth of the simple, isolated, and productive life. Jewett's characters gently reveal long-buried emotions: "I always liked Nathan," says Mrs. Todd, a widow. "But this pennyr'yal always reminded me, as I'd sit and gather it and hear him talkin'--it always reminded me of --the other one." Viewing her as "Antigone alone on the Theban plain," Jewett endows Mrs. Todd and other humble characters with mythic grandeur, celebrating the emotional complexity beneath their New England bluntness and humor.

The Country of the Pointed Firs secured a place for Jewett in the American literary canon. She was praised--and somewhat pigeon-holed--during her lifetime as a leader in the "local-color" movement of regional realism. Jewett's reputation was enhanced by her friend Willa Cather, whose preface to the 1925 edition of Pointed Firs aligns Jewett's text with Nathaniel Hawthorne's The Scarlet Letter and Mark Twain's Huckleberry Finn. Feminist critics have since championed her writing for its rich account of women's lives and voices. Jewett never abandoned her primary subject, the fruitful interdependence of community life. Counseling Cather in 1908 to write from her "own quiet centre of life," Jewett followed the success of Pointed Firs with further sketches and another novel, The Tory Lover (1901). Following a spinal concussion received from a carriage accident in 1902, Jewett's writing was limited to correspondence with friends. Three months after being paralyzed by a stroke, she died in South Berwick.

Bibliography

The bulk of Jewett's letters is at Houghton Library, Harvard University; the Society for the Preservation of New England Antiquities; and Colby College, Waterville, Maine. Collections of her correspondence include Letters of Sarah Orne Jewett (1994); Letters, ed. Richard Cary (1956; rev. ed., 1967); and Letters of Sarah Orne Jewett, ed. Annie Fields (1911). For a listing of primary texts see Gwen L. Nagel and James Nagel, Sarah Orne Jewett: A Reference Guide (1978), as well as Clara C. Weber and Carl J. Weber, A Bibliography of the Published Writings of Sarah Orne Jewett (1949). Paula Blanchard, Sarah Orne Jewett: Her World and Her Work (1994), contains black and white plates of Jewett and her contemporaries. Earlier biographies include F. O. Matthiessen, Sarah Orne Jewett (1929), John Eldridge Frost, Sarah Orne Jewett (1960), and Josephine Donovan, Sarah Orne Jewett (1980). M. A. de Wolfe Howe, Memories of a Hostess (1922), depicts the Jewett-Fields friendship. Collected shorter criticism includes Cary, ed., Appreciation of Sarah Orne Jewett (1973); Gwen Nagel, ed., Critical Essays on Sarah Orne Jewett (1984); and June Howard, ed., New Essays on "The Country of the Pointed Firs" (1994). Selected readings of Jewett's work include Willa Cather, Not under Forty (1936); Sarah Way Sherman, Sarah Orne Jewett: An American Persephone (1989); and Margaret Roman, Sarah Orne Jewett: Reconstructing Gender (1992).

Margaret A. Amstutz

Back to the top

Citation:

Margaret A. Amstutz. "Jewett, Sarah Orne";

http://www.anb.org/articles/16/16-00861.html;

American National Biography Online Feb. 2000.

Access Date: Fri Aug 09 2013 15:42:47 GMT-0400 (Eastern Standard Time)

Copyright © 2000 American Council of Learned Societies.

Person TypeIndividual

Last Updated8/7/24

Portsmouth, New Hampshire, 1835 - 1894, Appledore Island, Isle of Shoals, Maine

Martins Ferry, Ohio, 1837 - 1920, New York

Boston, 1861 - 1920, Chipping Campden, England

active Boston, 1845 - 1854

Deep River, Connecticut, 1868 - 1953, Princeton, New Jersey

Hyde Park, Massachusetts, 1869 - 1934, New York