Joseph Urban

Vienna, 1872 - 1933, New York City

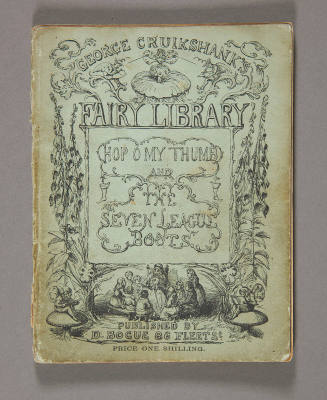

On completing his studies in 1893 Urban began work as a draftsman with the architect Ludwig Baumann, designing buildings for the Austrian government, including the Ministry of War and a new concert hall. Urban socialized with many members of the Viennese avant-garde, founding the Siebener Club in 1895. The Siebener Club consisted of, among others, his classmate Josef Maria Olbrich, the designer Josef Hoffmann and the painter Kolomon Moser. At this time Urban also began collaborating with the painter Heinrich Lefler, producing colorful book illustrations, calendars, postage stamps, and bank notes. These joint projects eventually won several awards, including the Austrian Gold Medal for Fine Arts and the Grand Prix at the Paris Exposition of 1900. He married Lefler's sister Mizzi in 1896, and they had two children.

In 1898 Urban was awarded his first architectural commission, the "Kaiser's Bridge," an arched pyramidal structure linking Vienna's art museum and concert hall. Private commissions followed, including several residences, a castle for the Hungarian count Esterhazy, as well as the interior decoration for the Rathauskeller and Volkskeller in Vienna's new City Hall. In 1904, on the occasion of the Louisiana Purchase Exposition in St. Louis, Urban visited the United States for the first time, designing the installation of art and furniture for the Hagenbund, the artists' group he and Lefler had formed four years earlier. Housed in the Austrian Pavilion, the spare modern interior was awarded the fair's special gold medal.

Urban's remarkable gift for interior decoration and two-dimensional design gradually began to dominate his work. In Vienna he began designing stage sets for the Burgtheater and the Royal Opera. Touring productions brought him international acclaim, and in 1911 he was invited to become artistic director of the Boston Opera, designing thirty productions during the next three years. In 1915 he moved to New York, beginning a long and fruitful relationship with the city's cultural elite.

With an office in Manhattan and a studio near his home in Yonkers, Urban was a staggeringly prolific designer. From 1914 to 1931 he designed scenery for the Ziegfeld Follies, an annual Broadway revue featuring music, dance, and elaborate costumes. In 1917 he began a simultaneous association with the Metropolitan Opera, mounting fifty-four lavish productions over the next sixteen years. Not only did he design and execute the sets, but he was also responsible for stage lighting and some direction. So great was Urban's public reputation that eventually he received equal billing with each opera's composer. In 1917 he became a U.S. citizen. That year he met the dancer Mary Porter Beegle, and after his divorce they married in 1919.

Impressed by Urban's opulent stage productions, William Randolph Hearst hired Urban to design sets and lighting for the first of thirty films for Cosmopolitan Productions. Many of these films were vehicles for the publisher's mistress, Marion Davies, including a number of historical spectacles in which buildings and streets from London and Paris were re-created by Urban's Yonkers workshop. Hearst also provided Urban with his first architectural commissions in New York. For gala premieres Urban was often asked to redesign the auditorium, creating new and evocative interiors that would compliment each film's setting.

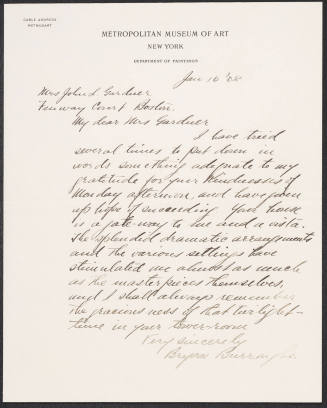

In 1925 Urban opened an architectural office in New York City. Although trained as an architect, more than two decades had passed since his first projects in Vienna. Perhaps the vast undertakings associated with film production had reawakened Urban's desire to build and create less ephemeral works. During the late 1920s he was particularly productive, designing stylish interiors for restaurants, hotels, and shops in a variety of styles ranging from neoclassical to modern. In addition, two of his domestic interiors were featured in the Metropolitan Museum of Art's The Architect and the Industrial Arts exhibition of 1929. He was also active in Palm Beach, Florida, where he designed and decorated several private homes and beach clubs, including the Oasis Club and the mansion Mar-a-Lago for Marjorie Merriweather Post.

Many of Urban's architectural commissions resulted from his work as a scenic designer. He built the Ziegfeld theater in 1927; its elliptical auditorium was celebrated for both its dramatic curved facade and its glittering decor with abundant mural decoration. Throughout these years Urban devoted much of his time to reforming American theater design. In his 1929 book Theaters Urban illustrated his philosophy with several innovative proposals, including those for the Metropolitan Opera and the Max Reinhardt Theater. Although neither of these projects were realized, both attempted to blur the boundary between stage and spectator, employing novel seating arrangements and numerous projecting secondary stages.

For Hearst, Urban also designed the International Magazine Building in New York in 1927-1928. The building's theatrical facade incorporated both allegorical statuary and oversized fluted columns topped by decorative urns. The New School for Social Research (1930), on the other hand, owed much less to his career as a scenic designer. Considered by many his architectural masterpiece, its cantilevered brick facade with horizontal bands of windows suggests a debt to recent developments in the European avant-garde, especially those in Germany. Urban created several wildly colorful and dramatic spaces within, especially the school's auditorium with its unique stepped-dome ceiling and a circular dance studio.

In the last years of his life Urban's output was particularly varied. In addition to continuing to design for the New York stage, he was awarded an honorable mention for his entry for the Palace of the Soviets competition (1931) and served as chief adviser for color and lighting at Chicago's Century of Progress exposition in 1933. He died in New York City. Although never a member of an identifiable school or movement, for two decades Urban was a major contributor to American culture, creating fanciful and often extravagant settings for the stage, the cinema, and urban life. While few of these sets and interiors survive, Urban was an architect and designer of immense talent, enjoying exceptional popular success in both Europe and North America.

Bibliography

The Joseph Urban archive, containing papers, architectural plans, drawings, photographs, and stage models, is located in Columbia University's Avery Library for Art and Architecture. For a full account of Urban's life, see Randolph Carter and Robert Reed Cole, Joseph Urban: Architecture, Theater, Opera, Film (1994), and Otto Teegen, "Joseph Urban," Architecture 69 (May 1934): 250-56. For a selective bibliography, see Joseph Urban and American Theater Architecture (1985). Obituaries are in the New York Times and the New York Herald Tribune, both 11 July 1933.

Matthew A. Postal

Back to the top

Citation:

Matthew A. Postal. "Urban, Joseph";

http://www.anb.org/articles/17/17-00883.html;

American National Biography Online Feb. 2000.

Access Date: Tue Aug 06 2013 11:42:06 GMT-0400 (Eastern Standard Time)

Copyright © 2000 American Council of Learned Societies.

Person TypeIndividual

Last Updated8/7/24

Villers-Cotterêts, France, 1802 - 1870, Dieppe, France

New York, 1875 - 1956, Cornish, New Hampshire

Hyde Park, Massachusetts, 1869 - 1934, New York

Martins Ferry, Ohio, 1837 - 1920, New York

Coventry, England, 1847 - 1928, Tenterden, England