Roger Fry

Middlesex, 1866 - 1934, London

Early years and education

Born into a Quaker family whose affiliation to the Society of Friends could be traced back to the seventeenth century on both sides, Roger Fry received a fairly strict upbringing, which emphasized moral rectitude and intellectual rigour. There was little in his education to prepare him for a career in the visual arts. After initial years of home schooling, Fry attended St George's preparatory school, Ascot, from 1877 to 1881, and went on to Clifton College, Bristol. He achieved high results and won a science exhibition at King's College, Cambridge, in 1884, where he began studying natural sciences the following year. His father, whose own success on the bench had been achieved at the expense of an early calling in zoology, hoped that Fry would embrace a scientific profession.

At Cambridge contact with men of a freethinking turn of mind and with philosophical and artistic interests helped Fry's personality to come into its own. A close acquaintance was John McTaggart, a friend from Clifton who was to become a prominent Hegelian philosopher, and whose atheism may have contributed to dampening Fry's faith. With Goldsworthy Lowes Dickinson, a young political science lecturer, Fry maintained an intimate, lifelong friendship. All three were members of the élite Conversazione Society, also known as the Apostles. Fry's participation in the moral debates of the society and encounters with such anti-establishment figures as Edward Carpenter and George Bernard Shaw confirmed a disposition for rational analysis and a desire to challenge received opinion. Meanwhile his growing interest in art was encouraged by his friendship with C. R. Ashbee, the future arts and crafts designer, who was then a regular sketching companion. Fry's contacts with the new Slade professor of fine art, John Henry Middleton, were a further influence in this respect.

Beginnings in painting and criticism

After a first in both parts of his tripos (1887, 1888), but the failure of two half-hearted applications for fellowships, Fry abandoned the idea of a scientific career, choosing instead to train as a painter. He left Cambridge in 1889 and spent the next two years in London, receiving tuition from Francis Bate, who was then honorary secretary of the New English Art Club (NEAC), the main alternative exhibiting society to the Royal Academy. Early in 1892 Fry spent two months studying at the Académie Julian in Paris. Although a painting of that period, Blythburgh, the Estuary (exh. 1892; priv. coll.), points to some familiarity with the works of the Nabis, he remained little acquainted with the contemporary French art scene. The mediation of Walter Sickert, whose evening classes he started attending the next year, probably did more to familiarize him with certain aspects of modern French painting, notably with the work of Degas.

In London Fry moved in anti-academic circles, frequenting artists and critics like Walter and Bernhard Sickert, Philip Wilson Steer, William Rothenstein, Alfred Thornton, and D. S. MacColl. He became a member of the NEAC in 1893, exhibiting there regularly until 1908 and frequently sitting on its selection jury from 1900.

Fry's tastes then were not those of a revolutionary. He had a distrust of impressionism for its lack of structural design; he also had mixed feelings about J. A. M. Whistler, admiring his landscapes more than his free treatment of sitters. His initial ambivalence towards the doctrine of ‘art for art's sake’ can be felt in his first substantial article, a review of George Moore's Modern Painting (Cambridge Review, 22 June 1893, 417–19). Similarly, Fry's early practice as a painter—classical landscapes in oils and watercolours pointing back to Claude, Poussin, and Thomas Girtin—reveals a reluctance to take up a modern idiom (The Pool, oil on canvas, exh. 1899; priv. coll.). While the watercolours brought some success (a one-man show at the Carfax Gallery in 1903), the oils were often seen as laboured and verging on pastiche. His style was much freer in portraiture. The full-length portrait Edward Carpenter (exh. 1894; NPG) deserved the praise it eventually attracted. Several portraits are held in the National Portrait Gallery, London.

The classicism of Fry's painting style at this time also reflects an immersion in the works of the Italian school, the result of two long stays in Italy in 1891 and 1894. During these tours, and a third, prolonged one in 1897–8, he made the acquaintance of a number of Renaissance specialists: John Addington Symonds, Gustavo Frizzoni—a disciple of Morelli—and most importantly Bernard Berenson, who directed Fry's first steps towards connoisseurship. Berenson's own approach to works, based on a response to form, undoubtedly guided Fry in this direction. The trips also furnished him with material for lectures and articles, as well as for his first book, Giovanni Bellini (1899), an insightful monograph on an artist who had previously been little studied.

Much to his regret, Fry was never in a position to support himself by painting, but he had an exceptional gift for criticism, and was to be remembered as an enthralling lecturer, with a deep, mellifluous voice. His first lectures, on Italian Renaissance art, were given in 1894 in the Cambridge University extension scheme. Other courses, and innumerable single lectures, would follow, taking him all over Britain—and occasionally abroad—and contributing to building his reputation as an authority. The venues were varied, including local art societies as well as university lecture halls; later, during the 1930s, Fry repeatedly filled the 2000-seat auditorium of the Queen's Hall. His subjects ranged from the analysis of a specific artist or school to discussions of aesthetics and of the methods of art history. The need to support a family, after his marriage on 3 December 1896 to Helen (1864–1937), a painter of some promise (the daughter of Joseph Coombe, a corn merchant), and the births of his son and daughter (1901 and 1902 respectively), had made him dependent on lecturing and publications for a regular income. This necessity became more pressing when his wife, who had begun to suffer from undiagnosed schizophrenia in 1899, was committed to an institution in 1910. Fry would remain married to her until his death.

The publication of Giovanni Bellini secured for Fry the job of art critic for The Pilot (1899). In 1901 he wrote an account of the various schools of Italian art for Macmillan's Guide to Italy and joined the staff of the weekly Athenaeum, an influential organ of British cultural life. He contributed substantial exhibition and book reviews, and commented on the policies of art institutions. Fry wrote authoritatively in a clear, flowing style, analysing technique in a lively manner and with a painter's eye. Form and composition were always important concerns, though less prominently so than later in his career, for he still mainly regarded their power as being that of expressing a given dramatic or psychological content. His interest in aesthetics comes to the fore in his annotated edition of Sir Joshua Reynolds's Discourses (1905).

In 1903 Fry helped to launch the monthly Burlington Magazine. He contributed penetrating analyses of individual works and artists, frequently suggesting new attributions. Editorial standards were high, and the articles, focusing mainly on ancient art, well illustrated. Fry helped to secure funds from American donors at an early stage; he was joint editor between 1909 and 1918, encouraging articles on modern art, and remained on the magazine's consultative committee until his death. Fry also wrote for The Nation from 1910 onwards, and published in a variety of other magazines on an occasional basis.

Fry and institutions

Fry's evident scholarly merits and the reputation he had acquired as an expert might rapidly have made him a strong candidate for a museum directorship, or a Slade professorship at Oxford or Cambridge. However, his relations with institutions were not of a kind to attract a consensus of approval. He was outspoken in his criticism of the Royal Academy—helping, for instance, to publicize its notorious mismanagement of the Chantrey bequest in 1903–4—and regularly complained in print about the National Gallery's acquisition policy. In consequence, his hopes of a Slade chair repeatedly met resistance and it was not until 1933 that he obtained that at Cambridge. As for museums, there was a missed opportunity early in 1906, when he was unable to accept the offer of the directorship of the National Gallery, London, having already committed himself to the role of curator of paintings at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. Later, when the directorship of the Tate Gallery was offered to him in 1911, he felt that the salary was too low, and declined.

Fry held his first post at the Metropolitan Museum until 1907. When family commitments became too pressing for a full-time role in New York, he became the museum's European adviser. His responsibility for developing the museum's collections, especially in Italian art, had to be reconciled with his former activism in England to resist the sale to America of works held in British private collections—the collective effort had led, in 1903, to the creation of the National Art Collections Fund. In 1910 Fry was dismissed from his post; with characteristic outspokenness, he had reproached the president of its board of trustees, the millionaire John Pierpont Morgan, for keeping for himself a work which Fry had secured for the museum. Fry's contempt for wealthy philistines, of whom he saw Morgan as the epitome, was frequently expressed in his correspondence and essays.

Post-impressionism and formalist criticism

In 1910 Fry publicly embraced the cause of modern French art, organizing the famous ‘Manet and the Post-Impressionists’ exhibition at London's Grafton Galleries. He had coined the term ‘post-impressionism’ with reference to the art of Cézanne, Gauguin, Van Gogh, and their followers, who included Matisse, Derain, and Picasso, with a view to underlining the distinctiveness of the newer artists' aims. Fry's familiarity with modern French art had been gradually asserting itself from 1906 onwards, a development which coincided with his growing interest in aesthetics. In ‘An essay in aesthetics’ (1909, repr. in Vision and Design, 1920), he had set out a way of responding to art that was based on form—on the analysis of design and its constituent ‘emotional’ elements, including ‘line’, ‘mass’, and ‘colour’. For Fry the post-impressionist artists were motivated by a similar conception of painting, favouring the expressive arrangement of form over the creation of a realistic illusion: ‘They do not seek to imitate form, but to create form; not to imitate life, but to find an equivalent for life’ (Fry, Vision and Design, 167). For Fry the post-impressionists had recovered the thread of artistic tradition, lost in the pursuit of realism.

‘Manet and the Post-Impressionists’ had a profound influence. Before the First World War London hosted a string of shows devoted to modern continental and British art, and Fry spared no effort to write and lecture about the new styles. In a ‘Second Post-Impressionist Exhibition’, also held at the Grafton Galleries, in 1912, he endeavoured to show how young British artists had responded to, and adopted, the new plastic idiom. While his formalist approach provided a theoretical legitimation of abstraction, his principal interest remained in figuration; he admired Matisse and Derain, and acknowledged the genius of Picasso, but had little interest in cubism, still less in futurism or expressionism. Fry was fascinated by Cézanne's treatment of space; for him Cézanne had succeeded in ‘us[ing] the modern vision with the constructive design of the old masters’ (Fry, Vision and Design, 202). The appeal of Cézanne is reflected in Fry's paintings of that decade, for example Quarry, Bo Peep Farm, Sussex (1918; Sheffield City Art Galleries).

Fry's new role as champion of the Paris avant-garde was accompanied by major changes in his life. He found himself out of key with the critics and painters with whom he had associated through the NEAC, but was rejuvenated by close contact with the younger generation of artists, whose work he did his best to promote. Through his friendship with the painter Vanessa Bell and her husband, Clive, whom he had met early in 1910, he became a key figure of the circle of artists and writers known as the Bloomsbury group. His theories exerted a major influence on Clive Bell, whose polemic Art (1914) was something of a post-impressionist manifesto, and whose theory of ‘significant form’ was in turn to stimulate Fry's aesthetic speculations. Fry's closeness to Vanessa Bell was both artistic and sentimental. She and Fry were lovers from 1911 to 1913, and he was lastingly affected by their separation, although they remained friends.

The year 1913 also saw the launch of Fry's Omega Workshops, a decorative art venture employing some twenty artists. It was an ideal platform for experimentation in abstract design, and for cross-fertilization between fine and applied arts. Omega attracted an exceptional range of talent: besides Fry, Vanessa Bell, and Duncan Grant, artists initially associated with it included Wyndham Lewis, Frederick Etchells, and Henri Gaudier-Brzeska. However, in spite of a number of commissions for interior design, the company survived the war years with difficulty, and closed in 1919.

Maturity

Fry's strong affinities with France led him to divide much of his time after the First World War between London, Paris, and Provence. Provence was a place for rest and painting, while in Paris he had numerous contacts with artists, dealers, and experts. He also sent works to the Salon d'Automne regularly between 1920 and 1926. Fry was on good terms with the artists Jean Marchand and André Derain, who both visited him in London, and enjoyed friendships with the writers Charles Vildrac, André Gide, and, above all, Charles and Marie Mauron, with whom he eventually bought a farm in Provence (1931). He had a good command of French, and his enthusiasm for French culture led him to undertake translations of poems, notably by Stéphane Mallarmé (1936), as well as of publications on art. Maurice Denis's 1907 article on Cézanne, which Fry translated for the Burlington Magazine (1910), was an important source for his own interpretation of the artist. Fry also translated two books on aesthetics by Charles Mauron (1927, 1935).

Vision and Design, a collection of essays which appeared in 1920, set a pattern for the format of Fry's publications—with a few exceptions, his books were revised transcripts of single or collected articles and lectures. Vision and Design achieved immediate popularity, and has rarely been out of print. Other important collections, also mixing aesthetics, criticism, and art history, are Transformations (1926) and the posthumously published Last Lectures (1939). Longer studies appeared in monograph form, including Cézanne (1927)—a justly celebrated work—and Henri Matisse (1930).

In the last years of his life Fry was busy writing, lecturing, painting, travelling, and sitting on committees. In 1931 a retrospective exhibition at the Cooling Galleries in London was well received, whereas his previous shows had failed to attract much praise. A series of twelve BBC broadcasts made between 1929 and 1934 shows that Fry remained an educationist at heart, taking a step-by-step approach to explanation and avoiding jargon. In line with his belief that art appreciation depends more on a ‘sensibility’ to form than on erudition, he encouraged receptiveness to art objects from non-Western traditions. He insisted that African sculpture was as deserving of study as Greek sculpture, and that anyone could respond to the aesthetic appeal of ancient Chinese vases. Throughout his life, however, Fry never ceased to puzzle over the status of representation, and its relation to aesthetic value. Eventually retreating from the more radical implications of formalism—which had led him, in the 1920s, to disqualify paintings seeking a narrative effect from the sphere of the visual arts—Fry came to embrace the idea that painting had a fundamentally ‘double’ nature. He presented Rembrandt and Giorgione, painters for whom he had the highest admiration, as ‘simultaneously attaining to an extreme poetic exaltation and achieving a great plastic construction and bringing about, moreover, a complete fusion of the two’ (Fry, ‘The Double Nature of Painting’, 1933; repr. 1969, 371).

Academic recognition came at last with the award of an honorary fellowship of King's College, Cambridge (1927), an honorary LLD of Aberdeen University (1929), and the Cambridge Slade professorship (1933). In his private life Fry found stability and happiness with Helen Anrep (1885–1965), his companion from 1926 until his death. He died at the Royal Free Hospital, London, on 9 September 1934, from complications after a fall in his flat caused a broken thigh. He was cremated on 13 September. There was no religious service, but a memorial service was held on 19 September at King's College chapel, Cambridge, where his ashes were interred.

Status and reputation

In 1939 Kenneth Clark credited Roger Fry with having brought about a change in taste in Britain (introduction to Fry, Last Lectures, ix). By introducing post-impressionist painting, and a critical terminology to make sense of it, Fry had indeed done more than any other critic to draw British art into modernist styles. Until surrealism and abstract art imposed themselves as the new avant-garde in the 1930s with the critical support of Herbert Read, Fry remained the best-known British advocate of modern art. Readers valued his insight and independence of mind, and an approach to criticism that Fry himself characterized as ‘experimental’ (Transformations, 1), based on a receptiveness to new ideas, and a willingness to submit conclusions to continual revision.

Less positive assessments have also been made. Fry's contemporaries sometimes charged him with having used his influence within artists' societies to promote his immediate entourage, and overly favoured the imitation of French styles. Later commentators have reproached him for failing to acknowledge a specifically British school. However, it must be pointed out that even those British artists who claimed a distinctive national identity were inextricably bound up with the international avant-garde. Fry's efforts to publicize British art—including work by artists associated with vorticism—internationally (Paris, 1912, 1927; Zürich, 1918) were real enough, even if they encountered little success.

The rise of Marxist theory, and of iconology, obscured the strengths of Fry's type of formalism, while subsequent assessment of his work has been complicated by the frequent confusion, among critics of formalism, of Fry's ideas with those of Clive Bell. Serious analysis of the ‘Bloomsbury’ thinkers has in general suffered from the tendency to consider them as all of a piece—a coterie to be celebrated or condemned. Nevertheless, the publication of two biographies of Fry—first by Virginia Woolf, and more recently by Frances Spalding—as well as of previously uncollected writings, and the mounting, since his death, of several exhibitions examining his achievement as painter, critic, and art historian (for example ‘Vision and Design: The Life, Work and Influence of Roger Fry, 1866–1934’, Arts Council, 1966; ‘Art Made Modern: Roger Fry's Vision of Art’, Courtauld Inst., 1999), testify to the major place which twentieth-century criticism continued to ascribe to Fry.

Anne-Pascale Bruneau

Sources

F. Spalding, Roger Fry: art and life (1999) · V. Woolf, Roger Fry: a biography, ed. D. F. Gillespie (1995) · Letters of Roger Fry, ed. D. Sutton, 2 vols. (1972) · D. Laing, Roger Fry: an annotated bibliography of the published writings (1979) · DNB · A.-P. Bruneau, ‘Roger Fry, Clive Bell: genèse d'une esthétique post-impressionniste’, doctoral diss., Université Paris 10–Nanterre, 1995 · R. Fry, Vision and design, ed. J. B. Bullen (1981) · R. Fry, ‘The double nature of painting’, Apollo, 89 (1969), 362–71 · F. Rutter, Art in my time (1933) · K. Clark, introduction, in R. Fry, Last lectures (1939) · articles on R. E. Fry as a painter, 1906–33, King's Cam., Roger Fry MSS, 10/2 · C. Green, ed., Art made modern: Roger Fry’s vision of art (1999) [exhibition catalogue, Courtauld Inst., London, 15 Oct 1999–23 Jan 2000] · R. Shone and others, The art of Bloomsbury: Roger Fry, Vanessa Bell and Duncan Grant (1999) [exhibition catalogue, London, San Marino, CA, and New Haven, CT, 4 Nov 1999–2 Sept 2000] · Vision and design: the life, work and influence of Roger Fry, 1866–1934 (1966) [with essays by Q. Bell and P. Troutman; exhibition catalogue, London and Nottingham, March–May 1966] · A. Fry, ed., A memoir of the Rt Hon. Sir Edward Fry (1921) · b. cert. · m. cert. · d. cert.

Archives

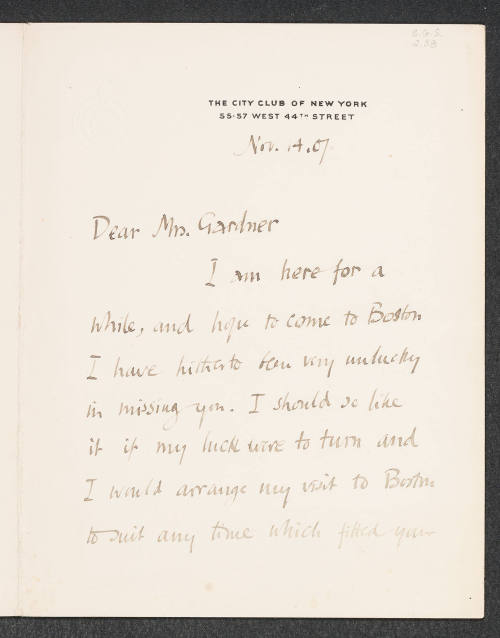

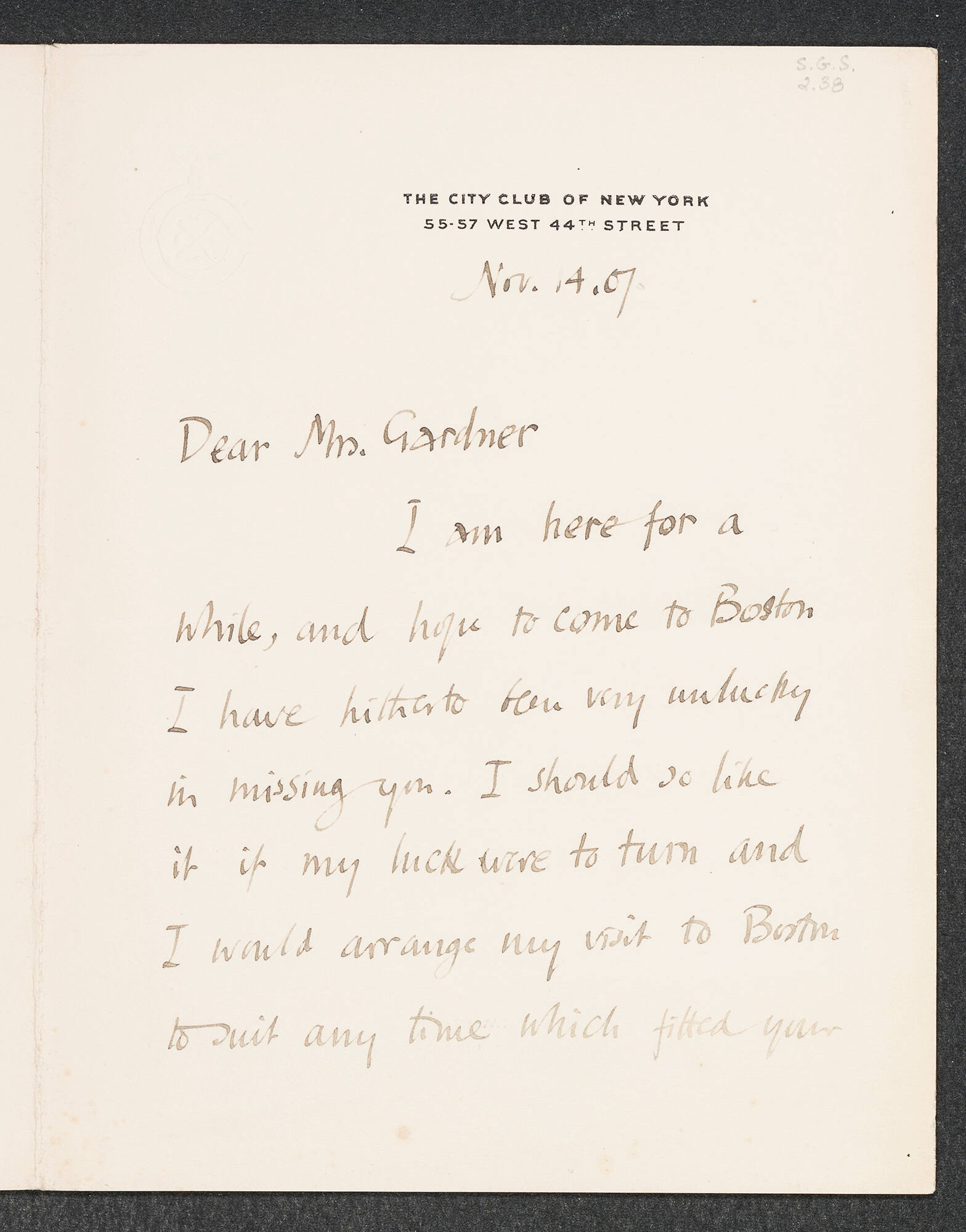

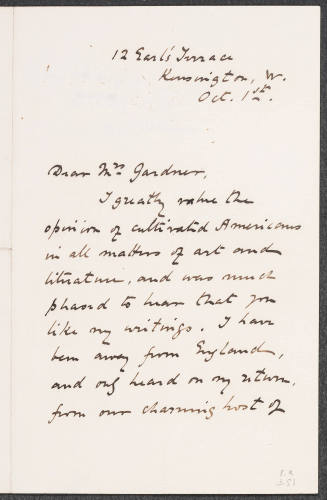

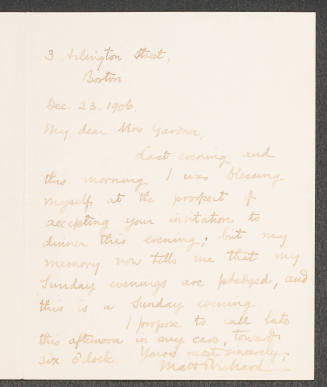

King's AC Cam., corresp. and papers :: BL, corresp. with Sidney Cockerell, Add. MS 52715 · BL, letters to George Bernard Shaw, Add. MS 50534 · Bodl. Oxf., letters to Arthur Ponsonby · Harvard U., Houghton L., letters to Sir William Rothenstein · Harvard University, near Florence, Italy, Center for Italian Renaissance Studies, letters to Bernard Berenson and Mary Berenson · King's AC Cam., corresp. with C. R. Ashbee; corresp. mainly with E. F. Bulmer; letters to John Maynard Keynes; letters to Nathaniel Wedd · LUL, letters to Thomas Sturge Moore · Tate collection, letters to Simon Bussy [photocopies] · U. Glas. L., letters to D. S. MacColl · U. Sussex, letters, literary MSS, to Clive Bell and Vanessa Bell; corresp. with Virginia Woolf · UCL, corresp. with Arnold Bennett

Likenesses

photographs, c.1872–1901, repro. in Spalding, Roger Fry · photograph, c.1872–1932, repro. in Woolf, Roger Fry · group portrait, photograph, c.1893, repro. in Green, ed., Art made modern · double portrait, photograph, c.1897 (with Helen Fry), Tate collection · A. Broughton, photograph, c.1900, NPG · photograph, c.1911, Tate collection · W. Sickert, ink caricature, c.1911–1912, Islington Public Libraries, London · V. Bell, oils, 1912, NPG; repro. in R. Shone, Bloomsbury portraits (1976) · double portrait, photograph, 1912 (with Sickert), repro. in R. Shone, Bloomsbury portraits (1976) · group portrait, photograph, 1912, Tate collection · portraits, c.1912–1923, repro. in Shone and others, Art of Bloomsbury · M. Beerbohm, pencil and watercolour caricature, 1913, King's Cam. · A. L. Coburn, photogravure, 1913, NPG · group portrait, photograph, 1913, repro. in Spalding, Roger Fry · photograph, c.1913–1919, repro. in Sutton, ed., Letters of Roger Fry · A. C. Cooper, sepia-toned print, 1918, NPG · R. Fry, self-portrait, oils, 1918, King's Cam. · M. Gimond, bronze head, 1920, NPG · J. Marchand, crayon drawing, 1920, NPG · R. Tatlock, photograph, c.1920, repro. in Spalding, Roger Fry · M. Beerbohm, pencil and watercolour caricature, c.1920–1921, priv. coll. · Quiz [P. Evans], pen-and-ink caricature, 1922 · H. Tonks, caricature in oils, c.1923, priv. coll. · R. Fry, self-portrait, oils, c.1926, repro. in Woolf, Roger Fry · photograph, c.1928, Tate collection · probably V. Bell, photograph, 1930–32, Tate collection · R. Fry, self-portrait, oils, c.1930–1934, NPG · Lenare, photograph, c.1930–1934, NPG · M. Beerbohm, pen and watercolour caricature, 1931, NPG · Ramsey & Muspratt, two bromide prints, 1932, NPG · V. Bell, double portrait, oils, c.1933 (with Julian Bell), King's Cam.; repro. in Shone and others, Art of Bloomsbury · V. Bell, oils, 1933, King's Cam. · group portrait, photograph, 1933, repro. in Q. Bell, Virginia Woolf (1976) · R. Fry, self-portrait, oils, 1934, King's Cam. · M. Beerbohm, caricature, Indiana University, Bloomington, Lilly Library; repro. in M.-A. Caws and S. B. Wright, Bloomsbury and France (2000) · Q. Bell, double portrait, photograph (with J. Bell), repro. in M.-A. Caws and S. B. Wright, Bloomsbury and France (2000) · W. Roberts, pencil caricature, Jason and Rhodes Gallery, London · R. Strachey, oils, NPG · caricature etching, University of Manchester · double portrait, photograph (with J. Coatmellec), King's Cam. · double portrait, photograph (with Marie Mauron), King's Cam.

Wealth at death

£21,449 12s. 6d.: probate, 13 Dec 1934, CGPLA Eng. & Wales

© Oxford University Press 2004–13

All rights reserved: see legal notice Oxford University Press

Anne-Pascale Bruneau, ‘Fry, Roger Eliot (1866–1934)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn, May 2010 [http://proxy.bostonathenaeum.org:2113/view/article/33285, accessed 8 Aug 2013]

Roger Eliot Fry (1866–1934): doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/33285

Person TypeIndividual

Last Updated8/7/24

Bradford, Yorkshire, 1872 - 1945, Far Oakridge

London, 1843 - 1932, Godalming, England

London, 1880 - 1969, Rodmell, East Sussex

Walmer, England, 1844 - 1930, Oxford, England

Coventry, England, 1847 - 1928, Tenterden, England

Somerset, 1865 - 1936, Buckinghamshire

Wavertree, England, 1850 - 1933, London