Reinhold Friedrich Alfred Hoernlé

Bonn, Germany, 1880 - 1943, Johannesburg

His father, (Augustus Frederic) Rudolf Hoernlé (1841–1918), Indologist and philologist, was born in Secundra, Agra, India, on 19 October 1841, the son of Christian Theophilus Hoernlé (1804–1882), one of the early missionaries sent to India under the auspices of the Church Missionary Society. He was educated in Europe at schools in Esslingen and Stuttgart, and the universities of Basel, Tübingen (DPh, 1872), and London. He went to India in 1865 as a Church Missionary Society missionary at Meerut and in 1869 was appointed professor of philosophy and Sanskrit at Jai Narayan's College in Benares. While on leave in England (1874–7) he completed a seminal work on vernacular languages of north India. In 1877 he married Sophie Fredericke Louise, daughter of R. Romig of Bonn; R. F. A. Hoernlé was their only son. A. F. R. Hoernlé returned to Calcutta, where he was principal of the Cathedral Mission College. In 1881 he joined the Indian educational service and became principal of the Calcutta Madrasa, a position he held until his retirement to England in 1899. He worked on editions and translations of newly discovered texts, most notably the Bower manuscript, a fifth-century birch-bark text in Sanskrit. He also produced a number of important studies of central Asian texts and was a primary decipherer of Khotanese. He served as secretary (1889–92) and president (1897) of the Asiatic Society of Bengal. In 1912 he was made an MA by decree by Oxford University. He died at his home, 8 Northmoor Road, Oxford, on 12 November 1918.

Like his father, R. F. A. Hoernlé was a British subject by birth and spent his early years in India. He was educated first in Germany at the Gymnasium Ernestinum in Gotha and the Gymnasium Pforte in Naumburg before proceeding to Balliol College, Oxford, in 1899, to prepare for a career in the Indian Civil Service. Influenced by his tutor, J. A. Smith, and the master of Balliol, Edward Caird, Hoernlé turned to philosophy. After gaining a second in classical moderations (1901) he took a first in literae humaniores (1903), and was awarded the Locke scholarship in mental and moral philosophy in 1903. In 1904 he was elected to a senior demyship at Magdalen College, where he studied for a BSc (completed in 1907), but in late 1905 moved to the University of St Andrews to serve as assistant to the professor of moral philosophy, Bernard Bosanquet.

Recommended by Caird, Bosanquet, and Smith, as well as by F. H. Bradley and Henry Jones, Hoernlé was appointed professor of philosophy at the South African College in 1908. From 1912 until 1914 he held the newly established professorship at Armstrong College, Newcastle (England). On 23 March 1914 Hoernlé married Agnes Winifred Tucker (1885–1960), a former philosophy student at South African College, and the daughter of the South African senator William Kidger Tucker. She later became a leading ethnographer and the doyenne of South African anthropologists. They had one son, Alwyn (1915–1991). In the summer of 1914 Hoernlé was appointed assistant professor of philosophy at Harvard University, where he was able to engage at first hand some of the leading American philosophers. In 1920, however, he returned to his former chair at Newcastle. The ostensible reason for this was his wife's health, though it also likely that it had to do with his disappointment at not being promoted at Harvard.

Hoernlé left Newcastle in 1923 to succeed John Macmurray as professor of philosophy at the University of the Witwatersrand in Johannesburg, South Africa, where Winifred Hoernlé was appointed to a post in anthropology. With the exception of visiting professorships at Bowdoin College, Maine (1926), and at the University of Southern California (1930), he spent little time outside South Africa until his death.

Hoernlé's early work was in metaphysics, epistemology, and philosophical psychology, and in 1916 he and his wife completed an authorized translation of Rudolf Steiner's Die Philosophie der Freiheit (‘The philosophy of freedom’). Hoernlé was particularly concerned with two issues: the relation between the mental and the physical (focusing on volition and mental states), and the current debates between idealists and the ‘new’ realists. He believed he could address these issues through the ‘empirical’ statement of idealism or ‘speculative philosophy’ represented by Bosanquet. In his Studies in Contemporary Metaphysics (1920) Hoernlé presented essays on scientific method and the ‘mechanism versus vitalism’ controversy, insisting that, in biology at least, teleology is dominant over mechanism. His Studies reflected a systematic philosophy, showing that ‘experience, taken as a whole, gives us clues which, rightly interpreted, lead to the perception of ... a graded order of varied appearances [in the universe]’ (p. v). It also exhibited his ‘synoptic’ approach, ‘which itself rests on the assumption that truth has many sides, and that to the whole truth on any subject every point of view has some contribution to make’ (‘On the way to a synoptic philosophy’, 138).

Hoernlé's Matter, Life, Mind, and God (1923), based on extramural lectures given in Newcastle to a popular audience, similarly discussed the limitations of both mechanistic and contemporary behaviouristic theories. Critics were somewhat receptive of the book, noting especially Hoernlé's ‘limpid clearness’ in style. In 1924 he published a short volume, Idealism as a Philosophical Doctrine, expanded in 1927 as Idealism as a Philosophy. Designed initially as a ‘map’ to guide students through the different schools of ‘idealism’ still current in Anglo-American philosophy, the key chapters trace the distinction between the idealism of Berkeley on the one hand and of Kant, Hegel, and their successors on the other. The volume was dedicated to the memory of Bosanquet—Hoernlé described himself as a Bosanquetian—but his views are best understood as being inspired by, rather than extending, Bosanquet's work.

When Hoernlé arrived at Witwatersrand in 1923 his teaching included courses in logic and psychology. Practical concerns, however, were never far from his mind, and he and his wife soon became actively involved in social issues. For Hoernlé there was a close relation between speculative thought and ‘the practical task of meeting the varied incidents of human life with steadfast wisdom’ (Hoernlé, Race and Reason, p. xvi). His wife was a pioneering social anthropologist and one of the first scholars of Bantu studies in South Africa, and Hoernlé himself developed an interest in the black peoples of the region and the impact of western civilizations on them. He also became fluent in Afrikaans so that he could give courses of lectures and public addresses throughout the country. He was active in university affairs, and in 1927 was controversially passed over for the principalship of Witwatersrand; he was the senate's proposed candidate, but the university council appointed Humphrey Rivaz Raikes.

Hoernlé was a founding member (1929), member of the executive (from 1932), and president (from 1934) of the South African Institute of Race Relations. He was also chairman of the Bantu Men's Social Centre in Johannesburg, of the Johannesburg Joint Council of Europeans and Natives, and of the Society of Christians and Jews (from 1937), which was founded to counter antisemitism in South Africa. In addition from 1934 he was a government-appointed member of the South African Council for Educational and Social Research—the first national research grant council—and one of the six South African delegates to the British Commonwealth Relations conference held near Sydney in September 1938. During the Second World War he was the initiator of the Army Educational Corps of which he became honorary lieutenant-colonel.

Despite his extensive committee work Hoernlé still published occasionally on philosophical topics. The focus of his writing, however, particularly after 1931, was increasingly applied—for example on the concept of race, race relations, and how local cultures might develop in relation to dominant cultures. Hoernlé's view was decidedly ‘liberal’, and some of his essays were collected and republished after his death as Race and Reason (1945). Perhaps the best example of Hoernlé's social and political views is found in his South African Native Policy and the Liberal Spirit, the Phelps-Stokes lectures at the University of Cape Town for 1939, which he repeated in Afrikaans at the University of Stellenbosch. Hoernlé's political philosophy was attentive to individual interests, but he believed that classical liberalism would not work in multicultural states like South Africa. Drawing on the idealist notion of positive liberty, Hoernlé saw that freedom required allowing social groups to develop their unique characters, but held that native cultures would tend to assimilate into the ‘western’.

A ferocious critic of the policy of racial segregation proposed by the government of J. B. M. Hertzog from 1924 onwards, Hoernlé viewed segregation as entrenching white domination and the exploitation of the non-European peoples. Despite an earlier optimism, his 1939 Phelps-Stokes lectures gained him a reputation for taking a pessimistic view of race relations in South Africa. He argued that in the face of white resistance, racial integration or assimilation—involving a non-racial franchise and the removal of the colour-bar in industry—was unrealistic in the immediate future. So long as the economy of white South Africa depended upon cheap black labour drawn from the native reserves, segregation would be inherently exploitative. He noted that liberals could consider the option of attempting to reconstitute original, racially distinct, communities that would permit genuine social, economic, and cultural development, and work to ensure that one group would not be dominated by another, but he saw this as ‘utterly impossible’ and ‘impracticable’ (Race and Reason, 103, 108). Presciently, perhaps, Hoernlé saw that change in race relations would come about as a result of ‘world forces’, not from within South African society (ibid., 167). In the short term, then, the only hope of protecting the non-European races lay in the notion of temporary trusteeship, represented by pragmatic, ameliorative measures in such fields as education, health, housing, and recreation. In 1941 he had an important correspondence with Geoffrey Hare Clayton, Anglican archbishop of Cape Town, in which both sought to resolve these dilemmas. Praise for Hoernlé in one of the most popular novels about the South African situation, Alan Paton's Cry the Beloved Country (1948), gives an indication of the widespread recognition of his leadership in the movement against segregation.

Hoernlé's death, following a heart attack and brief illness, in Johannesburg on 21 July 1943, was attributed largely to the stress of his extensive administrative work. His remains were cremated, following a funeral service at St Mary's Cathedral, Johannesburg, at Braamfontein crematorium. Former students collected some of his early writings in a volume entitled Studies in Philosophy (1952). Although the political impact of Hoernlé's work was significant in his time, the philosophical impact of his views on culture and community remains relatively limited.

William Sweet

Sources

R. F. A. Hoernlé, Studies in philosophy, ed. D. S. Robinson (1952) · University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, archives · R. F. A. Hoernlé, Race and reason: being mainly a selection of contributions to the race problem in South Africa, ed. I. D. MacCrone (1945) · WW (2002) · WWW · DSAB, 3.397–9 · E. Rosenthal, ed., Encyclopedia of southern Africa, 6th edn (1973) · R. F. A. Hoernlé, ‘On the way to a synoptic philosophy’, Contemporary British philosophy: personal statements, ed. J. H. Muirhead, 2nd ser. (1925), 129–56 · J. Laird, Mind, 53 (July 1944), 285–7 · Rand Daily Mail (22 July 1943) · University of the Witwatersrand: calendar (1923–43) · G. Watts Cunningham, ‘Review of Matter, life, mind, and God by R. F. Alfred Hoernlé’, Philosophical Review, 33/2 (March 1924), 208–9 · B. B. Kaplan, Race relations in South Africa, as illustrated by the writings of A. W. Hoernlé, R. F. A. Hoernlé and J. D. Rheinallt Jones: a bibliography (Johannesburg, 1971) · W. Sweet, British idealism in South Africa [forthcoming] · B. K. Murray, Wits, the early years: a history of the University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, and its precursors, 1896–1939 (1982) · B. K. Murray, Wits, the ‘open’ years: a history of the University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, 1939–1959 (1997) · A. Paton, Apartheid and the archbishop: the life and times of Geoffrey Clayton, archbishop of Cape Town (1973) · WWW [A. F. R. Hoernlé] · G. A. Grierson, Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society (1919), 114–24 [A. F. R. Hoernlé] · The Times (15 Nov 1918) [A. F. R. Hoernlé] · U. Sims-Williams, ‘Augustus Frederic Rudolf Hoernlé’, Encyclopaedia Iranica, 12, no. 4 · census returns, 1901 [A. F. R. Hoernlé]

Archives

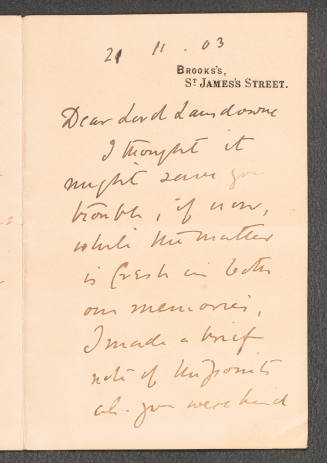

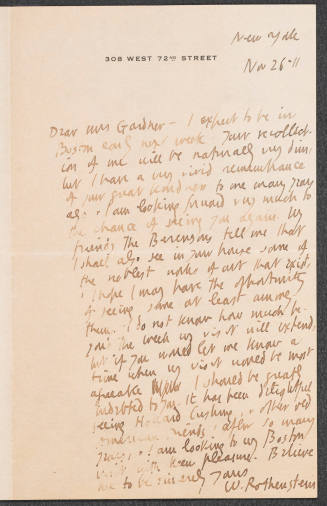

University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg :: BL, A. F. R. Hoernlé's notes and lectures, Add. MSS 40002–40003 · BL OIOC, A. F. R. Hoernlé's notes on Indian texts, mainly related to medicine, MS Eur. F 302 · Bodl. Oxf., A. F. R. Hoernlé's corresp. · University of the Witwatersrand, South African Institute of Race Relations archive, corresp. of R. F. A. Hoernlé, AD 1623

Likenesses

photograph, repro. in Hoernlé, Studies in philosophy, frontispiece · photograph, repro. in Forum: South Africa's Independent Journal of Opinion (3 July 1943) · portrait, University of the Witwatersrand, convocation office

Wealth at death

£2859 13s. 0d.—A. F. R. Hoernlé: probate, 5 Feb 1919, CGPLA Eng. & Wales

© Oxford University Press 2004–13

All rights reserved: see legal notice Oxford University Press

William Sweet, ‘Hoernlé, (Reinhold Friedrich) Alfred (1880–1943)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, May 2006 [http://proxy.bostonathenaeum.org:2113/view/article/94419, accessed 8 Aug 2013]

(Reinhold Friedrich) Alfred Hoernlé (1880–1943): doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/94419

(Augustus Frederic) Rudolf Hoernlé (1841–1918): doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/95621

Person TypeIndividual

Last Updated8/7/24

Terms

Giessen, Hesse-Durmstadt, 1854 - 1925, Sturry Court, Kent

Salisbury, New Brunswick, Canada, 1846 - 1922, London

London, 1858 - 1927, near Worksop, England

Bradford, Yorkshire, 1872 - 1945, Far Oakridge

Portsmouth, England, 1828 - 1909, Box Hill, England

Torquay, Devon, England, 1821 - 1890, Trieste, Italy

Vicksburg, Mississippi, 1859 - 1931, Washington, D.C.

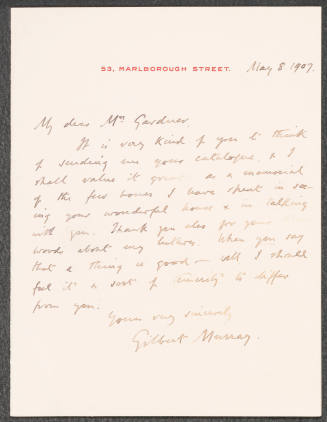

Sydney, Australia, 1866 - 1957, Boars Hill, England

Cincinnati, 1857 - 1930, Washington, D.C.