Image Not Available

for George Saintsbury

George Saintsbury

Southampton, England, 1845 - 1933, Bath, England

Saintsbury, George Edward Bateman (1845–1933), literary scholar and historian, was born in Lottery Hall, Southampton, on 23 October 1845, the second son (there were also two daughters) of George Saintsbury (d. 1860), then secretary and superintendent of Southampton docks, and his wife, Elizabeth Wright (d. 1877). His parents went to London, where, in 1850, his father became secretary of the East India and China Association. Saintsbury was educated at King's College School, London, and entered Merton College, Oxford, as a classical postmaster in 1863. He was awarded a first class in classical moderations (1865) and a second class in literae humaniores (1867). While at college his chief friend was Mandell Creighton. Having after several attempts failed to obtain a fellowship, he left Oxford in 1868, and on 2 June of that year married Emily Fenn King (d. 1924), daughter of Henry William King, surgeon, of Southampton; the couple had two sons.

Saintsbury became a schoolmaster, at first for a few months at Manchester grammar school and then as senior classical master at Elizabeth College, Guernsey (1868–74), where he read widely, especially in French literature, and sent his first reviews to The Academy. In 1874 he moved to Moray, Scotland, as headmaster of a new private foundation, the Elgin Educational Institute. It did not prosper, and he returned to London in 1876 to live by his pen, with a brief spell in 1877 on the staff of the Manchester Guardian.

Saintsbury's first essay of note, a signed article on Baudelaire, appeared in the Fortnightly Review (October 1875), and on the invitation of the editor, John Morley, it was followed in 1878 by eight essays on contemporary French novelists, reprinted as a volume in 1891. It was as a critic of French literature that he first made his name. He contributed over thirty articles on the subject to the ninth edition of the Encyclopaedia Britannica (1875–89; repr. as a separate volume, 1946) and wrote a Primer (1880) and a Short History (1881) of French literature. Together with his anthologies and further essays these provided the English reader with a sound factual introduction based on fresh and voluminous reading. His views often ran counter to the accepted verdicts of French critics.

Saintsbury was also hard at work in English literature, not just in reviewing but writing books and essays. His Dryden (1881), for the English Men of Letters series, was a much needed study of a favourite author; it was followed by an eighteen-volume reprint, with new introductions, of Sir Walter Scott's Dryden, which suffered through delays in publication (1881–93) and through using an unrevised text. By 1887, when Saintsbury's History of Elizabethan Literature was published, his main interests had turned from French literature to English, though he still oversaw, with his own critical introductions added, a forty-volume translation of Balzac (1895–8). From 1886 onward he contributed articles on English authors to Macmillan's Magazine; those which were collected in volumes of Essays in English Literature, 1780–1860 (1890, 1895) and Miscellaneous Essays (1892) brought his name before a large reading public. In the 1880s and 1890s there was a flood of editions, anthologies, and selections, all with critical introductions which showed the breadth of his reading and the vigour of his opinions. He also contributed to most of the popular series of the time, including the short books Marlborough (for English Worthies, 1885), Manchester (for Historic Towns, 1887), and Lord Derby (for The Queen's Prime Ministers, 1892).

This great body of critical work had been exceeded in sheer bulk by Saintsbury's work as a journalist between 1876 and 1895. With Andrew Lang and Robert Louis Stevenson, he was a prominent contributor to London (1877–9) under W. E. Henley's editorship. He wrote for the Pall Mall Gazette while Morley remained its editor, and for the St James's Gazette and many other papers. His main work as a journalist, however, was on the Saturday Review, of which he was assistant editor from 1883 to 1894, when he left on a change of ownership. The independent toryism of the Saturday Review was never more vigorous than in the years when Saintsbury became a seasoned Fleet Street commentator. He made a speciality of the fight against Gladstone's Irish policy, and saved the paper from accepting Richard Pigott's forged ‘Parnell letters’, which duped The Times (G. E. B. Saintsbury, Scrap Book, 3, 1924, 274). ‘In my twenty years of journalism’, he wrote, ‘I must have written the equivalent of at least a hundred volumes of the “Every Gentleman's Library” type—and probably more’ (ibid., 1, 1922, x).

In September 1895 Saintsbury was able to withdraw from the precarious existence of a journalist and reviewer on appointment (in succession to David Masson) to the regius professorship of rhetoric and English literature at the University of Edinburgh. While obliged to face the disorder of a very large first-year ‘ordinary’ class, he could also take advantage of the small number of honours students to concentrate on substantial literary works. His influence grew steadily and he became a prominent figure in the university; the twenty years of his professorship form one of the most notable periods in the history of a famous chair.

Having conscientiously left off reviewing, Saintsbury's substantial books came out with notable rapidity. The Short History of English Literature (1898), wholly new in design and substance, was written in less than a year (and later revised to meet criticisms of detail). Thereafter he worked on A History of Criticism and Literary Taste in Europe from the Earliest Texts to the Present Day (3 vols., 1900–04), supplemented by Loci critici (1903), a collection of illustrative passages. Then came the three-volume History of English Prosody from the Twelfth Century to the Present Day (3 vols., 1906–10), with an illustrative Historical Manual (1910) and a natural but novel sequel in A History of English Prose Rhythm (1912). Before he was appointed to the chair he had planned a twelve-volume Periods of European Literature, and he contributed three volumes to the series: The Flourishing of Romance and the Rise of Allegory (1897), The Earlier Renaissance (1901), and The Later Nineteenth Century (1907). As well as writing or editing books on Scott (1897) and Arnold (1899), and The English Novel (1913), editions of the plays of Dryden (1904) and Shadwell (1912), a collection entitled Minor Poets of the Caroline Period (3 vols., 1905–21), and introductions to the Oxford Thackeray (17 vols., 1908), he delivered many major lectures to prominent learned societies. The main task of the later years of his professorship was his contribution of twenty-one chapters to the Cambridge History of English Literature (1907–16). When he retired from the chair in 1915, at the age of seventy, his unremitting energy had enabled him to accomplish much more than he had foreseen on his appointment. He signalled his retirement by writing The Peace of the Augustans: a Survey of Eighteenth Century Literature as a Place of Rest and Refreshment (1916), relaxed in manner and an antidote to wartime preoccupations, which long enjoyed popularity with a general readership.

On leaving Edinburgh, where he had resided at Murrayfield House (1896–1900) and 2 Eton Terrace (1900–15), Saintsbury sold up his cellar and much of his library and moved briefly to Southampton before settling at Bath in rooms at 1 Royal Crescent. A two-volume History of the French Novel (1917–19) was his last big book, but he continued industriously as an essayist. Notes on a Cellar-Book (1920), an allusive causerie on wine rather than a systematic treatise, brought him fame in gastronomic circles, and in 1931 a dining society, the Saintsbury Club, was founded in his honour. Three Scrap Books followed, in 1922–4, spicing his recollections (he forbade any biography of himself) with social and political observations. His strong and consistent conservatism, which in the first period of his journalism had necessarily been anonymous, showed itself unashamedly in his later general writings. His high-churchmanship, with a special reverence for Edward Pusey, was not much discussed, but he was a tory who gloried in the name and admitted that he would have opposed every great reform since 1832.

Saintsbury remained a voracious reader, and he could not abandon writing. ‘The professor ceasing, the reviewer revives’, he wrote in 1923. A Letter Book was published in 1922, and Collected Essays and Papers in 1923–4, in four volumes which presented only a selection from his total output. A Consideration of Thackeray (1931) gathered his writings on one of his most admired authors, and there were further Prefaces and Essays gathered (by Oliver Elton) in 1933, with George Saintsbury: the Memorial Volume (1945) and A Last Vintage: Essays and Papers by George Saintsbury (1950), both edited by his pupil Augustus Muir, adding to the many collections.

Saintsbury's long experience as a journalist gave him great facility in the composition even of learned commentary. His writing is generally vigorous and readable, but his literary output was too large for him to exercise full care with his prose style, which too easily became involved and densely allusive, or with factual details, where reviewers were ready to pounce. As a critic he was pre-eminently a ‘taster’, who said what it was he liked and why he liked it. He looked for the characteristic quality and found it in style rather than in form or substance. The true and only test of literary greatness, he said, was the transport, the absorption of the reader. Interested as he was in the lives of authors, as his many introductory memoirs show, his attention never strays from the primary importance of their works. His historical backgrounds are kept in their place as backgrounds; and he avoided a statement of any philosophy of literature. The History of Criticism is now seen to be weakened by its lack of a conceptual framework. As a historian of literature he had to deal with movements and tendencies, and here his remarkable knowledge made the task easy for him, and congenial. While never subordinating style to substance, he enjoyed tracing the fortunes of a literary form and showing the changes in its appeal to the reader. Yet even in his histories he is never better than when dealing with individual works or authors. He was the doyen of academic critics of his day, wide-ranging and with a gusto that had not been exceeded since Hazlitt.

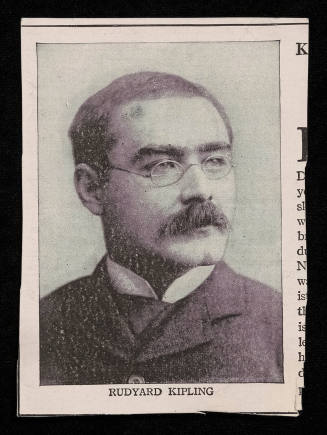

In old age Saintsbury was much reverenced by the reading public as a sage, and he received many honours from his colleagues, including an address on his seventy-seventh birthday in 1922 from over 300 friends and admirers. He held several honorary doctorates and was elected a fellow of the British Academy in 1911. He appreciated above all his honorary fellowship (1911) of Merton College, Oxford. The college owns a characterful portrait of him (1923) by William Nicholson, which, with its skull-cap, large pondering brow, small spectacles, and long straggling beard, bespeaks the venerable savant. George Saintsbury died at his home in Royal Crescent, Bath, on 28 January 1933 and was buried in the old cemetery in Southampton, his birthplace.

Alan Bell

Sources

A. Blyth Webster, ‘George Saintsbury’, in George Saintsbury: the memorial volume, ed. A. Muir and others (1945), 23–64 · A last vintage: essays and papers by George Saintsbury, ed. A. Muir (1950) [incl. bibliography by W. M. Parker] · O. Elton, ‘George Edward Bateman Saintsbury, 1845–1933’, PBA, 19 (1933), 325–44 · DNB · D. Jones, King of critics: George Saintsbury, 1845–1933 (1992) · J. Gross, The rise and fall of the man of letters: aspects of English literary life since 1800 (1969) · H. Orel, Victorian literary critics (1984), 151–76 · b. cert. · m. cert. · d. cert.

Archives

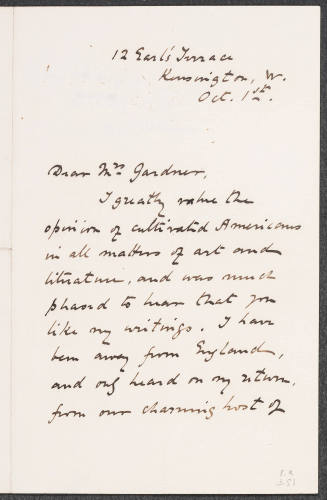

Merton Oxf., letters · NL Scot., corresp. and literary papers · NL Scot., account book · NRA, corresp. and literary papers :: BL, corresp. with Macmillans, Add. MSS 55019–55020 · BL, letters to A. R. Waller, Add. MS 43681 · Bodl. Oxf., letters to Bertram Dobell · JRL, letters to W. E. Axon · LUL, letters to Austin Dobson and David Hannay · LUL, letters to Brenda E. Spender · Merton Oxf., letters to William Hunt and wife · NAM, letters to Earl Roberts · NL Scot., Blackwood MSS, MSS, letters · NL Scot., letters to D. N. Smith · Queen's University, Belfast, letters to Helen Waddell with anthology compiled for her · Royal Society of Literature, London, letters to the Royal Society of Literature · U. Edin. L., corresp. with Charles Sarolea · U. Leeds, Brotherton L., letters to Sir Edmund Gosse · UCL, letters to David Hannay

Likenesses

W. Stoneman, photograph, 1919, NPG [see illus.] · W. Nicholson, oils, 1923, Merton Oxf.

Wealth at death

£9655 19s. 5d.: resworn probate, 18 March 1933, CGPLA Eng. & Wales

© Oxford University Press 2004–16

All rights reserved: see legal notice Oxford University Press

Alan Bell, ‘Saintsbury, George Edward Bateman (1845–1933)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004 [http://proxy.bostonathenaeum.org:2055/view/article/35908, accessed 23 Oct 2017]

George Edward Bateman Saintsbury (1845–1933): doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/35908

Person TypeIndividual

Last Updated8/7/24

Terms

Carmarthen, Wales, 1833 - 1907, Llangunnor, Wales

Inverness, Scotland, 1877 - 1938, London

Dunbartonshire, Scotland, 1800 - 1859, London

Wavertree, England, 1850 - 1933, London

Kolkata, India, 1811 - 1863, London