Harold Victor Bauer

New Malden, Kingston-upon-Thames, England, 1873 - 1951, Miami, Florida

On one occasion, when he was taken to play the piano for the Polish pianist Ignace Paderewski in London, the famous pianist said, "That is very nice, but you have a lot to learn"; Bauer replied, "I wish you could hear me play the violin, I can play it better." Paderewski subsequently introduced Bauer to his friend, violinist Wladyslaw Gorski, who, after hearing Bauer play both violin and piano told him, "You play better than I do. I think, however, that you play the piano better than you play the violin." Gorski then asked Bauer to accompany him in playing a sonata by César Franck (Musical Quarterly 29 [Apr. 1943]: 159). Bauer agreed; meanwhile Paderewski, who was in the process of learning a number of piano concertos, asked Bauer to play the orchestral reductions on the second piano and to practice the works with him at his home. This association with Paderewski later prompted Bauer to acknowledge that he "learned a great deal by being in the presence of this great master" but that "it cannot be said that I was his pupil" (Musical Quarterly 29 [Apr. 1943]: 159).

During the winter of 1894-1895, Bauer toured in Russia as accompanist for the singer Louise Nicholson, also filling out the programs with piano solos. Subsequently he returned to Europe, with Paris as a center, where he worked diligently to make a name for himself as a pianist. He realized that in order to overcome his technical deficiencies, he would need to find some means of making his playing acceptable without subjecting himself to the usual approach to technical study commonly undertaken by pianists--that is, evenness of scales, arpeggios, and "good tone." Accordingly, he decided that rather than practicing scales and other exercises, which had nothing to do with the piece at hand, he would devote himself entirely to developing his technic within the context of music itself, thereby refining his expressive powers, enhancing his phrasing, and discovering how "one note relates to other notes" (Cooke, p. 71). As he put it, "The only technical study of any kind I have ever done has been that technic which has had an immediate relation to the technical message of the piece I was studying" (Cooke, p. 65). His somewhat unorthodox approach of never studying technique independent of the musical piece produced such fine results that he became convinced that it was a mistake to practice technique at all "unless such practice should conduce to some definite, specific and immediate result" (Cooke, p. 66). As he explained to James Cooke,

Naturally, studying in this way required my powers of concentration to be trained to the very highest point. This matter of concentration is far more important than most teachers imagine. . . . Many pupils make the mistake of thinking that only a certain kind of music demands concentration, whereas it is quite as necessary to concentrate the mind upon the playing of a simple scale as for the study of a Beethoven sonata (Cooke, pp. 68-69).

Bauer adamantly believed that, correctly understood, "technic is art and must be studied as such. There should be no technic in music which is not music itself" (Cooke, p. 70).

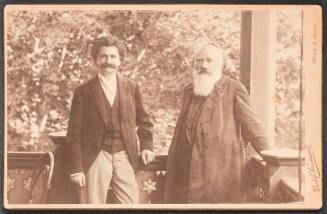

On 30 November 1900 Bauer played the Brahms D minor Piano Concerto with the Boston Symphony under the conductor Wilhelm Gericke. From 1901 through 1902 he played again in the United States with orchestras in many of the nation's principal cities, and in 1903 and 1904 he toured in Brazil. He played in the United States and Europe as soloist and chamber musician during the following ten years, appearing with such illustrious musicians as cellist Pablo Casals and violinists Fritz Kreisler and Jacques Thibaud. Later his duo piano recitals with pianist Ossip Gabrilowitsch became highly popular. The individuality, fire, and imagination that he brought to his playing earned Bauer unaminous praise from critics and colleagues as one of the most distinguished pianists of his day.

Following the outbreak of World War I, Bauer settled in New York and became an American citizen. In 1917 he helped organize the Manhattan School of Music and in 1919 he founded the Beethoven Association, a society organized "to bring together artists of established reputation with the object of giving an annual series of concerts in a spirit of artistic fraternity." Bauer was president of the Beethoven Society from its beginning until 1939, just before the society dissolved. During his presidency the society was celebrated for the artistic quality of its concerts, which featured many outstanding artists who performed free of charge in its programs. The proceeds from the performances went to such charitable purposes as furthering the publication of Alexander Thayer's Life of Beethoven, supporting the MacDowell Association, a center for the arts in Peterboro, New Hampshire, facilitating the extensions of public collections of Beethoveniana, furnishing manuscript scores by great composers and reference books on musical subjects for the Library of Congress and the New York Public Library, and contributing to the building of the Festspielhaus in Salzburg.

During the height of his career (1915-1935), Bauer made nearly two hundred records and several radio appearances. Later he gave private instruction in New York and conducted master classes at the leading music schools and conservatories throughout the United States. Bauer introduced Claude Debussy's works to English audiences and arranged compositions of J. S. Bach, Johannes Brahms, Henry Purcell, and Robert Schumann for piano. Through his leadership in the Beethoven Association of New York and the Friends of Music of the Library of Congress, he did much to encourage interest in chamber music in America.

His first wife, Marie Knapp, of Stuttgart, whom he married in 1906, died in 1940. He predeceased his second wife, Winnie Pyle. Both marriages were childless. Bauer died in Miami, Florida.

Bibliography

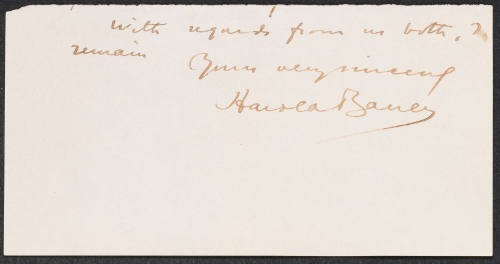

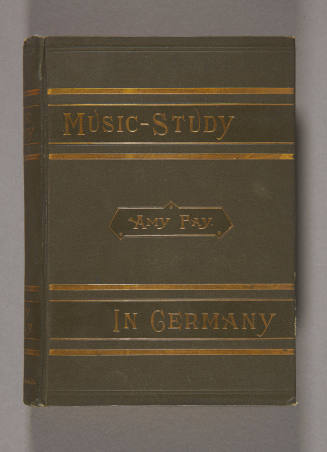

Bauer's papers are in the Library of Congress and include over 300 letters from friends and professional associates; 100 photographs; numerous concert programs, awards, press clippings, and lectures; printed music and holographs of piano arrangements; and the manuscript for his autobiography Harold Bauer, His Book (1948). Bauer's other works include "Self-Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man," Musical Quarterly 29 (Apr. 1943): 153-68, with photographs; "The Paris Conservatoire. Some Reminiscences," Musical Quarterly 33 (Oct. 1947): 533-42; and "Artistic Aspects of Piano Study," in James F. Cooke, Great Pianists on Piano Playing: Study Talks with Foremost Virtuosos (1917). Other information on Bauer and his career may be found in Clara Clemens, My Husband Gabrilowitsch (1938); Adella Prentiss Hughes, Music Is My Life (1947); Harold C. Schonberg, The Great Pianists: From Mozart to the Present (1987), with photographs; and Olga Samaroff Stowkowski, An American Musician's Story (1939).

Margaret William McCarthy

Citation:

Margaret William McCarthy. "Bauer, Harold Victor";

http://www.anb.org/articles/18/18-00076.html;

American National Biography Online Feb. 2000.

Access Date: Fri Aug 09 2013 10:26:15 GMT-0400 (Eastern Standard Time)

Copyright © 2000 American Council of Learned Societies.

Person TypeIndividual

Last Updated8/7/24

Terms

St. Petersburg, 1878 - 1936, Detroit

Edgeworth, Pennsylvania, 1862 - 1901, New Haven, Connecticut

El Vendrell, Catalonia, Spain, 1876 - 1973, San Juan

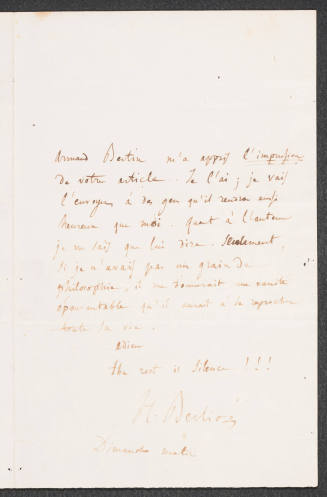

Bonn, Germany, 1770 - 1827, Vienna

La Côte-Saint-André, France, 1803 - 1869, Paris

Bayou Goula, Louisiana, 1844 - 1928, Watertown, Massachusetts

Hamburg, Germany, 1809 - 1847, Leipzig, Germany