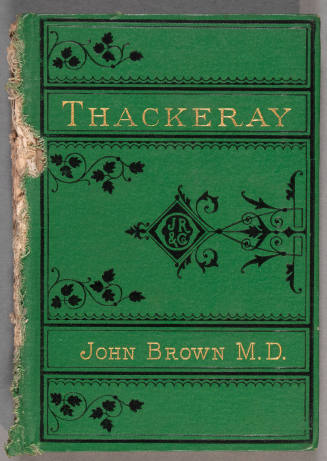

John Brown

Biggar, Lanarkshire, Scotland, 1810 - 1882

In the two later volumes of the ‘Horæ’ Brown's pen took a somewhat wider range. He had, we suppose, discovered his own strength in authorship, and found that he had other things in his mind besides medicine on which he had something to say. Poetry, art, the nature and ways of dogs, human character as displayed in men and women whom he had intimately known, the scenery of his native country with its associations romantic or tender—all these come in for review, and on all of them he writes with a curiously naïve and original humour, and, as it seems to us, a singularly deep and true insight. One great charm of his writings is that, as with those of Montaigne and Charles Lamb, much of his own character is thrown into his books, and in reading them we almost feel as if we became intimately acquainted with the author. And in private he did not belie the idea which his books convey of him. Few men have in life been more generally beloved, or in death more sincerely lamented. He had a singular power of attaching both men and animals to himself, and a stranger could scarcely meet with him even once without remembering him ever afterwards with interest and affection. In society he was natural and unaffected, with pleasantry and humour ever at command, yet no one could suspect any tinge of frivolity in his character. He had read very widely, had strong opinions on many questions both in literature and philosophy, possessed great knowledge of men, and had an unfailing interest in humanity. With all the tenderness of a woman, he had a powerful manly intellect, was full of practical sense, tact, and sagacity, and found himself perfectly at home with all men of the best minds of his time who happened to come across him. Lord Jeffrey, Lord Cockburn, Mr. Thackeray, Mr. Ruskin, Mr. Henry Taylor, and Mr. Erskine of Linlathan were all happy to number themselves among his most attached friends.

There was a strong countervailing element of melancholy in Brown's constitution, as in most men largely endowed with humour. This, we believe, showed itself more or less even in boyhood; but in the last sixteen years of his life it became occasionally so distressing as to necessitate his entire withdrawal for a time from society, and latterly induced him to retire to a great extent from the general practice of his profession. In the last six months of his life, however, his convalescence seemed to be so complete that his friends began to hope he had finally thrown off this tendency, and during the winter immediately preceding his death all his old cheerfulness and intellectual vivacity appeared to have returned; but in the beginning of May 1882 he caught a slight cold, which deepened into a severe attack of pleurisy, and carried him off after a short illness on the 11th of that month.

The first volume of the ‘Horæ Subsecivæ’ was published in 1858, the second in 1861, and a third in 1882, only a few weeks before Brown's death. They have all gone through numerous editions both in this country and in America, while ‘Rab and his Friends’ (first published in 1859) and other papers have appeared separately in various forms, and have had an immense circulation.

John Taylor Brown. "Brown, John (1810-1882)." Dictionary of National Biography, 1885-1900, Volume 07

Person TypeIndividual

Last Updated8/7/24

Bristol, 1840 - 1893, Rome

Horsham, 1792 - 1822, near Viareggio

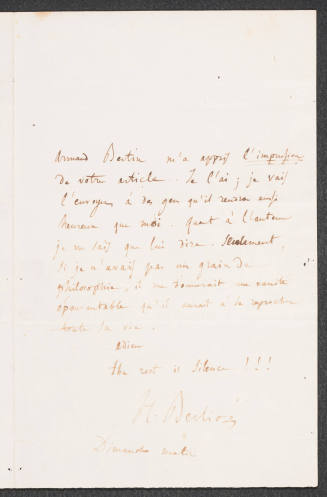

La Côte-Saint-André, France, 1803 - 1869, Paris

Kolkata, India, 1811 - 1863, London

Cambridge, Massachusetts, 1809 - 1894, Boston

Torquay, Devon, England, 1821 - 1890, Trieste, Italy

Walmer, England, 1844 - 1930, Oxford, England