Edwin Lawrence Godkin

1831 - 1902

After a short time with the Belfast Northern Whig Godwin went in November 1856 to the United States, and toured the southern states, observing the slave system. He reported for the Daily News, and was admitted to the bar of the state of New York in February 1858. He married at New Haven, on 29 July 1859, the ‘statuesquely attractive’ 22-year-old Frances (Fanny) Elizabeth, elder daughter of Samuel Edmund Foote of Cincinnati and New Haven, who had made his fortune as president of the Ohio Life Insurance and Trust Company: a financially advantageous marriage. They had a son, who survived Godkin, and two daughters, who predeceased him; his wife died on 11 April 1875. In 1860 he visited Europe for his health. While he was there the American Civil War broke out, and he supported the North, writing to the Daily News condemning the British policy on the Trent incident. On returning to the United States in September 1862, while continuing his reports to the Daily News, he wrote for the New York Times, the North American Review, and Atlantic Monthly. He also took charge for a short time of the Sanitary Commission Bulletin. In July 1865, with others, he established in New York an independent weekly journal, The Nation, and after the first year took it over almost entirely as his private venture. He edited and wrote much of it until 1881, when he sold it to the Evening Post, of which it became a kind of weekly edition. In 1883 he became editor-in-chief of both papers, retiring because of ill health in 1899. For most of this time his sub-editor was his friend W. P. Garrison, son of William Lloyd Garrison.

The politically independent The Nation inaugurated a new departure in American journalism and, though its circulation was relatively small, it influenced educated opinion. Its contributors included leading American and British men of letters. Leslie Stephen—who stayed with Godkin in New York in 1868 and considered him ‘a remarkably sensible, intelligent man’, and on politics ‘the most reasonable American I have seen’ (Maitland, 207)—was its English correspondent (1868–73).

Godkin's beliefs were those then common among educated persons. He believed the ‘Anglo-Saxon race’ would expand into Central America and dominate the Pacific, and he supported suppression of the Indian mutiny. He condemned the ‘carpetbagger’ regime in the southern states, and the corruption of U. S. Grant's administration. A moralist, concerned for the quality of government in the United States, he wanted rule by the ‘intelligent and virtuous classes’. He opposed national and municipal corruption, and demanded civil service reform and abolition of the ‘spoils system’ (by which politicians used civil service appointments to reward supporters). Believing immigration underlay corruption, he demanded an end to immigration from southern and eastern Europe, and tests of fitness to vote for immigrants and black people; he alleged in 1874 that the latter's intelligence was so low that they were ‘slightly above the level of animals’ (Armstrong, 105). He opposed women's suffrage, arguing that it would allow servant girls to outvote their mistresses, and criticized socialism. He opposed the Alaska purchase and American expansionism. Though he had previously favoured the Republicans, as a civil service reformer and free-trader in 1884 he supported Grover Cleveland's Democratic presidential candidature. His paper was the recognized organ of the independent ‘Mugwumps’ between 1884 and 1894. He opposed Cleveland's anti-British interference in 1895 in the Anglo-Venezuelan dispute. He attacked Tammany Hall (the immigrant-supported corrupt New York city government), publishing in the Evening Post biographies of its leaders, and was subjected to virulent abuse and libel actions by Tammany politicians. In December 1894, after Tammany's temporary defeat, partly due to his efforts, he was presented with a loving cup for his ‘fearless and unfaltering service to the city of New York’ (Ogden, Life and Letters, 2.181). He opposed Mahan's navalism, the Spanish-American War, the South African War, and the American annexation of Hawaii and the Philippines. He also opposed, on economic grounds, high tariffs, the silver policy, and bimetallism.

In 1870 Godkin declined an offer of the Harvard history professorship, and in 1875 moved to Cambridge, Massachusetts, returning to New York in 1877. In 1875 he became a member of a commission to ‘Plan for the government of cities in the State of New York’, which reported to the New York legislature in 1877. He married Katherine, daughter of Abraham Sands, on 14 June 1884; she survived her husband. In 1895 he was made an unpaid civil service commissioner. Godkin visited England in 1889, after twenty-seven years away. In June, through James Bryce, he met Gladstone, who denounced the Liberal Unionists ‘with curious fire, his eye glowing’ (Ogden, Life and Letters, 2.155). He liked England, and thereafter repeatedly visited; his enemies criticized his Anglophilia. Among his friends were Bryce, A. V. Dicey, and Henry James. He was, like his father, an advocate of Irish home rule, and contributed to the Liberal Handbook of Home Rule (1887) edited by Bryce. As home-ruler, free-trader, opponent of war and annexation, and advocate of honest and economical administration, he was in line with advanced British Liberals, and he criticized the Conservative leaders. His views were stated in his Reflections and Comments (1895), Problems of Modern Democracy (1896), and Unforeseen Tendencies of Democracy (1898). In June 1897 he was awarded an Oxford DCL: ‘the “blue ribbon” of the intellectual world, and very gratifying’ (ibid., 2.22). After serious illness in 1900, he sailed for England in May 1901, and died at Greenway House, Brixham, on the Dart in south Devon, on 21 May 1902; he was buried on 28 May in Hazelbeach churchyard, near Market Harborough, Northamptonshire. Bryce's inscription on his grave described him as a ‘Publicist, economist, moralist ... a steadfast champion of good causes and high ideals’ (ibid., 2.255).

Able, widely read, a trenchant writer, and a charming friend, Godkin worked for America but was never fully assimilated. Matthew Arnold considered him ‘a typical specimen of the Irishman of culture’ (Ogden, Life and Letters, 2.1). His political views, deemed by some Englishmen the ‘soundest’ and ‘sanest’ in America, were those of a philosophic radical, though in later and more pessimistic years ‘a disillusioned radical’ (ibid., 2.238); he remained an advanced Liberal of the period 1848 to 1870. Though lacking original ideas, he was an effective communicator and crusader for good government.

C. P. Lucas, rev. Roger T. Stearn

Sources

R. Ogden, Life and letters of Edwin Lawrence Godkin, 2 vols. (1907) · W. M. Armstrong, E. L. Godkin: a biography (1978) · R. Ogden, ‘Godkin, Edwin Lawrence’, DAB · J. Bryce, Studies in contemporary biography (1903) · The Times (23 May 1902) · Annual Register (1902) · private information (1912) · F. L. Mott, American journalism, rev. edn (New York, 1950) · Fifty years of Fleet Street: being the life and recollections of Sir John R. Robinson, ed. F. M. Thomas (1904) · J. F. Rhodes, Historical essays (1909) · Gladstone, Diaries · F. W. Maitland, The life and letters of Leslie Stephen (1906) · J. M. Blum and others, The national experience (1963)

Archives

Bodl. Oxf., letters to James, Viscount Bryce

Likenesses

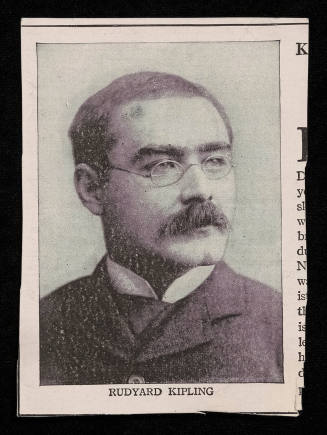

W. M. Hollinger, photograph, NPG SI · engraving (after photograph, 1870), repro. in Ogden, Life and letters of Edwin Lawrence Godkin

© Oxford University Press 2004–13

All rights reserved: see legal notice Oxford University Press

C. P. Lucas, ‘Godkin, Edwin Lawrence (1831–1902)’, rev. Roger T. Stearn, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn, Oct 2006 [http://proxy.bostonathenaeum.org:2113/view/article/33432, accessed 8 Aug 2013]

Edwin Lawrence Godkin (1831–1902): doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/33432

Person TypeIndividual

Last Updated8/7/24

Terms

Cambridge, 1827 - 1908, Cambridge

Martins Ferry, Ohio, 1837 - 1920, New York

Wavertree, England, 1850 - 1933, London

Salisbury, New Hampshire, 1782 - 1852, Marshfield, Massachusetts

Cambridge, Massachusetts, 1809 - 1894, Boston

Sydney, Australia, 1866 - 1957, Boars Hill, England